Table of Contents

All Surge Documents in one page

(slow load, ~86 pages)

Article 1-Solution As Big As Problem

A Solution As Big As The Problem

Michael P. Farris, JD, LLM, Convention of States Action — Senior Fellow for Constitutional Studies

We See Four Major Abuses Perpetrated by the Federal Government.

These abuses are not mere instances of bad policy. They are driving us towards an age of “soft tyranny” in which the government does not shatter men’s wills but “softens, bends, and guides” them. If we do nothing to halt these abuses, we run the risk of becoming nothing more than “a flock of timid and industrious animals, of which the government is the shepherd.”

(Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America,1840)

1. The Spending and Debt Crisis

The $17 trillion national debt is staggering, but it only tells part of the story. Under standard accounting practices, the federal government owes around $100 trillion more in vested Social Security benefits and other pro-grams. This is why the government cannot tax its way out of debt. Even if it confiscated everything, it would not cover the debt.

2. The Regulatory Crisis

The federal bureaucracy has placed a regulatory burden upon businesses that is complex, conflicted, and crushing. Little account-ability exists when agencies—rather than Congress—enact the real substance of the law. Research from the American Enterprise Institute shows that, since 1949, federal regulations have lowered the real GDP growth by 2% and made America 72% poorer.

3. Congressional Attacks on State Sovereignty

For years, Congress has been using federal grants to keep the states under its control. Combining these grants with federal mandates (which are rarely fully funded), Congress has turned state legislatures into their regional agencies rather than respecting them as truly independent republican governments.

A radical social agenda and an invasion of the rights of the people accompany all of this. While significant efforts have been made to combat this social erosion, these trends defy some of the most important principles.

4. Federal Takeover of the Decision-Making Process

The Founders believed that the structures of a limited government would provide the greatest protection of liberty. Not only were there to be checks and balances between the branches of the federal government, but power was to be shared between the states and federal government, with the latter only exercising those powers specifically granted in the Constitution.

Collusion among decision-makers in Washington, D.C., has replaced these checks and balances. The federal judiciary supports Congress and the White House in their ever-escalating attack upon the jurisdiction of the fifty states.

We need to realize that the structure of decision-making matters. Who decides what the law shall be is as important as what is decided. The protection of liberty requires a strict adherence to the principle that power is limited and delegated.

Washington, D.C., does not believe in this principle, as evidenced by an unbroken practice of expanding the boundaries of federal power. In a remarkably frank admission, the Supreme Court rebuffed a challenge to federal spending power, despite acknowledging that power had grown far beyond the bounds envisioned by the Founders.

What Does this Mean?

This is not a partisan issue. Washington, D.C., will never voluntarily relinquish meaningful power—no matter who is elected. The only rational conclusion is this: Unless some political force outside of Washington, D.C., intervenes, the federal government will continue to bankrupt this nation, embezzle the legitimate authority of the states, and destroy the liberty of the people. Rather than securing the blessings of liberty for future generations, Washington, D.C., is on a path that will enslave our children and grandchildren to the debts of the past. The problem is big, but we have a solution. Article V gives us a tool to fix the mess in D.C.

Our Solution Is Big Enough to Solve the Problem

Rather than calling a convention for a specific amendment, Convention of States Action (COSA) urges state legislatures to properly use Article V to call a convention for a particular subject—reducing the power of Washington, D.C. It is important to note that a convention for an individual amendment (e.g., a Balanced Budget Amendment) would be limited to that single idea. Requiring a balanced budget is a great idea that COSA fully supports. Congress, however, could comply with a Balanced Budget Amendment by simply raising taxes. We need spending restraints as well. We need restraints on taxation. We need prohibitions against improper federal regulation. We need to stop unfunded mandates.

A Convention of States needs to be called to ensure that we are able to debate and impose a complete package of restraints on the misuse of power by all branches of the federal government.

What Sorts of Amendments Could Be Passed?

The following are examples of amendment topics that could be discussed at a conven-tion of states:

- A Balanced Budget Amendment

- A redefinition of the General Welfare Clause (the original view was that the federal government could not spend money on any topic within the jurisdiction of the states)

- A redefinition of the Commerce Clause (the original view was that Congress was granted a narrow and exclusive power to regulate shipments across state lines–not all the economic activity of the nation)

- A prohibition on using international treaties and law to govern the domestic law of the United States

- A limitation on using executive orders and federal regulations to enact laws (since Congress is supposed to be the exclusive agency to enact laws)

- Imposing term limits on Congress and the Supreme Court

- Placing an upper limit on federal taxation

- Requiring the sunset of all existing federal taxes and a super-majority vote to replace them with new, fairer taxes

Of course, these are merely examples of what would be up for discussion. The Convention of States itself would deter-mine which ideas deserve serious consideration, and it would take a majority of votes from the states to formally pro-pose any amendments.

The Founders gave us a legitimate path to save our liberty by using our state governments to impose binding restraints on the federal government. We must use the power granted to the states in the Constitution.

Article 2 - The Lamp of Experience

The Lamp of Experience: Constitutional Amendments Work

Robert Natelson, Independence Institute’s Senior Fellow in Constitutional Jurisprudence and Head of the Institute’s Article V Information Center

Opponents of a Convention of States long argued there was an unacceptable risk that a convention might do too much. It now appears they were mistaken. So they increasingly argue that amendments cannot do enough.

The gist of this argument is that amendments would accomplish nothing because federal officials would violate amendments as readily as they violate the original Constitution.

Opponents will soon find their new position even less defensible than the old. This is be-cause the contention that amendments are useless flatly contradicts over two centuries of American experience — experience that demonstrates that amendments work. In fact, amendments have had a major impact on American political life, mostly for good.

The Framers inserted an amendment process into the Constitution to render the underlying system less fragile and more durable. They saw the amendment mechanism as a way to:

- correct drafting errors;

- resolve constitutional disputes, such as by reversing bad Supreme Court decisions;

- respond to changed conditions; and

- correct and forestall governmental abuse.

The Framers turned out to be correct, because in the intervening years we have adopted amendments for all four of those reasons. Today, nearly all of these amendments are accepted by the overwhelming majority of Americans, and all but very few remain in full effect. Possibly because ratification of a constitutional amendment is a powerful expression of popular political will, amendments have proved more durable than some parts of the original Constitution.

Following are some examples:

Correcting Drafting Errors

Although the Framers were very great people, they still were human, and they occasionally erred. Thus, they inserted into the Constitution qualifications for Senators,

Representatives, and the President, but omitted any for Vice President. They also adopted a presidential/vice presidential election procedure that, while initially plausible, proved unacceptable in practice.

The founding generation proposed and ratified the Twelfth Amendment to correct those mistakes. The Twenty-Fifth Amendment addressed some other deficiencies in Article II, which deals with the presidency. Both amendments are in full effect today.

Resolving Constitutional Disputes and Overruling the Supreme Court

The Framers wrote most of the Constitution in clear language, but they knew that, as with any legal document, there would be differences of interpretation. The amendment process was a way of resolving interpretive disputes.

The founding generation employed it for this purpose just seven years after the Constitution came into effect. In Chisholm v. Georgia, the Supreme Court misinterpreted the wording of Article III defining the jurisdiction of the federal courts. The Eleventh Amendment reversed that decision.

In 1857, the Court issued Dred Scott v. Sandford, in which it erroneously interpreted the Constitution to deny citizenship to African Americans. The Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment reversed that case.

In 1970, the Court decided Oregon v.Mitchell, whose misinterpretation of the Constitution created a national election law mess. A year later, Americans cleaned up the mess by ratifying the Twenty-Sixth Amendment.

All these amendments are in full effect today, and fully respected by the courts.

Responding to Changed Conditions

The Twentieth Amendment is the most obvious example of a response to changed conditions. Reflecting improvements in transportation since the Founding, it moved the inauguration of Congress and President from March to the January following election.

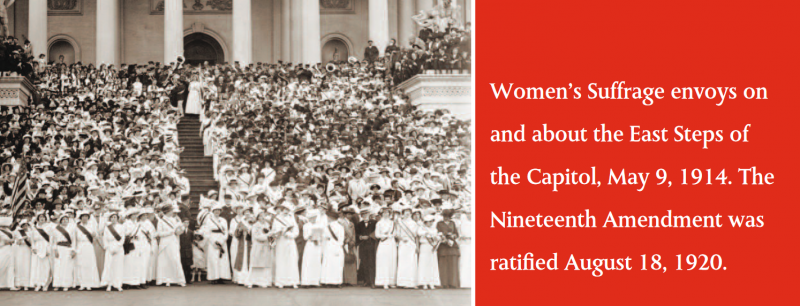

Similarly, the Nineteenth Amendment, which assured women the vote in states not already granting it, was passed for reasons beyond simple fairness. During the 1800s, medical and technological advances made possible by a vigorous market economy improved the position of women immeasurably and rendered their political participation far more feasible. Without these changes, I doubt the Nineteenth Amendment would have been adopted.

Needless to say, the Nineteenth and Twentieth Amendments are in full effect many years after they were ratified.

Correcting and Forestalling Government Abuse

Avoiding and correcting government abuse was a principal reason the Constitutional Convention unanimously inserted the state-driven convention procedure into Article V. Our failure to use that procedure helps explain why the earlier constitutional barriers against federal overreaching seem a little ragged. Before looking at the problems, how-ever, let’s look at some successes:

- We adopted the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, Fifteenth, and Twenty-Fourth Amendments to correct state abuses of power. All of these are in substantially full effect.

- In 1992, we ratified the Twenty-Seventh Amendment, 203 years after James Madison first proposed it. It limits congressional pay raises, although some would say not enough.

- In 1951, we adopted the Twenty-Second Amendment, limiting the President to two terms. Eleven Presidents later, it remains in full force, and few would contend it has not made a difference.

Now the problems: Because we have not used the convention process, the first 10 amendments (the Bill of Rights) remain almost the only amendments significantly limiting congressional overreaching. I suppose that if the Founders had listened to the “amendments won’t make any difference” crowd, they would not have adopted the Bill of Rights either. But I don’t know anyone to-day who seriously claims the Bill of Rights has made no difference.

“I have but one lamp by which my feet are guided; and that is the lamp of experience,” Patrick Henry said. “I know of no way of judging of the future but by the past.”

In this case, the lamp of experience sheds light unmistakably bright and clear: Constitutional amendments work.

Article 3 - Answering the Runaway Convention Myth

Can We Trust the Constitution? Answering The “Runaway Convention” Myth

By Michael Farris, JD, LLM

Some people contend that our Constitution was illegally adopted as the result of a “run-away convention.” They make two claims:

- The convention delegates were instructed to merely amend the Articles of Confederation, but they wrote a whole new document.

- The ratification process was improperly changed from 13 state legislatures to 9 state ratification conventions.

The Delegates Obeyed Their Instructions from the States

The claim that the delegates disobeyed their instructions is based on the idea that Congress called the Constitutional Convention. Proponents of this view assert that Congress limited the delegates to amending the Articles of Confederation. A review of legislative history clearly reveals the error of this claim. The Annapolis Convention, not Congress, provided the political impetus for calling the Constitutional Convention. The delegates from the 5 states participating at Annapolis concluded that a broader convention was needed to address the nation’s concerns. They named the time and date (Philadelphia; second Monday in May).

The Annapolis delegates said they were going to work to “procure the concurrence of the other States in the appointment of Commissioners.” The goal of the upcoming convention was “to render the constitution of the Federal Government adequate for the exigencies of the Union.”

What role was Congress to play in calling the Convention? None. The Annapolis delegates sent copies of their resolution to Congress solely “from motives of respect.”

What authority did the Articles of Confederation give to Congress to call such a Convention? None. The power of Congress under the Articles was strictly limited, and there was no theory of implied powers. The states possessed residual sovereignty which included the power to call this convention.

Seven state legislatures agreed to send delegates to the Constitutional Convention prior to the time that Congress acted to endorse it. The states told their delegates that the purpose of the Convention was the one stated in the Annapolis Convention resolution: “to render the constitution of the Federal Government adequate for the exigencies of the Union.”

Congress voted to endorse this Convention on February 21, 1787. It did not purport to “call” the Convention or give instructions to the delegates. It merely proclaimed that “in the opinion of Congress, it is expedient” for the Convention to be held in Philadelphia on the date informally set by the Annapolis Convention and formally approved by 7 state legislatures.

Ultimately, 12 states appointed delegates. Ten of these states followed the phrasing of the Annapolis Convention with only minor variations in wording (“render the Federal Constitution adequate”). Two states, New York and Massachusetts, followed the formula stated by Congress (“solely amend the Articles” as well as “render the Federal Constitution adequate”).

Every student of history should know that the instructions for delegates came from the states. In Federalist 40, James Madison answered the question of “who gave the binding instructions to the delegates.” He said: “The powers of the convention ought, in strictness, to be determined by an inspection of the commissions given to the members by their respective constituents [i.e. the states].” He then spends the balance of Federalist 40 proving that the delegates from all 12 states properly followed the directions they were given by each of their states. According to Madison, the February 21st resolution from Congress was merely “a recommendatory act.”

The States, not Congress, called the Constitutional Convention. They told their delegates to render the Federal Constitution adequate for the exigencies of the Union. And that is exactly what they did.

The Ratification Process Was Properly Changed

The Articles of Confederation required any amendments to be approved by Congress and ratified by all 13 state legislatures. Moreover, the Annapolis Convention and a clear majority of the states insisted that any amendments coming from the Constitutional Convention would have to be approved in this same manner—by Congress and all 13 state legislatures.

The reason for this rule can be found in the principles of international law. At the time, the states were sovereigns. The Articles of Confederation were, in essence, a treaty be-tween 13 sovereign nations. Normally, the only way changes in a treaty can be ratified is by the approval of all parties to the treaty.

However, a treaty can provide for some-thing less than unanimous approval if all the parties agree to a new approval process be-fore it goes into effect. This is exactly what the Founders did.

When the Convention sent its draft of the Constitution to Congress, it also recommended a new ratification process. Congress approved both the Constitution itself and the new process.

Along with changing the number of required states from 13 to 9, the new ratification process required that state conventions ratify the Constitution rather than state legislatures. This was done in accord with the preamble of the Constitution—the Supreme Law of the Land would be ratified in the name of “We the People” rather than “We the States.”

But before this change in ratification could be valid, all 13 state legislatures would also have to consent to the new method. All 13 state legislatures did just this by calling conventions of the people to vote on the merits of the Constitution.

Twelve states held popular elections to vote for delegates. Rhode Island made every voter a delegate and held a series of town meetings to vote on the Constitution. Thus, every state legislature consented to the new ratification process thereby validating the Constitution’s requirements for ratification.

Those who claim to be constitutionalists while contending that the Constitution was illegally adopted are undermining themselves. It is like saying George Washington was a great American hero, but he was also a British spy. I stand with the integrity of our Founders who properly drafted and properly ratified the Constitution.

Article 4 - Is the Second Amendment at Risk

An Open Letter Concerning The Second Amendment and The Convention of States Project

Our constitutional rights, especially our Second Amendment right to keep and bear arms, are in peril. With every tragic violent crime, liberals renew their demands for Congress and state legislatures to enact so-called “commonsense gun control” measures designed to chip away at our individual constitutional right to armed self defense. Indeed, were it not for the determination and sheer political muscle of the National Rifle Association, Senator Feinstein’s 2013 bill to outlaw so-called “assault weapons” and other firearms might well have passed. But the most potent threat facing the Second Amendment comes not from Congress, but from the Supreme Court. Four justices of the Supreme Court do not believe that the Second Amendment guarantees an individual right to keep and bear arms. They believe that Congress and state legislatures are free not only to restrict firearms owner-ship by law-abiding Americans, but to ban firearms altogether. If the Liberals get one more vote on the Supreme Court, the Second Amendment will be no more.

Constitutional law has been the dominant focus of my practice for most of my career as a lawyer, first in the Justice Department as President Reagan’s chief constitutional lawyer and the chairman of the President’s Working Group on Federalism, and since then as a constitutional litigator in private practice. For almost three decades, I have represented dozens of states and many other clients in constitutional cases, including many Second Amendment cases. In 2001, for example, I argued the first federal appellate case to hold that the Second Amendment guarantees every law-abiding responsible adult citizen an individual right to keep and bear arms. And in 2013 I testified before the Senate in opposition to Senator Feinstein’s anti-gun bill, arguing that it would violate the Second Amendment. So I am not accustomed to being accused of supporting a scheme that would “put our Second Amendment rights on the chopping block.” This charge is being hurled by a small gun-rights group against me and many other constitutional conservatives because we have urged the states to use their sovereign power under Article V of the Constitution to call for a convention for proposing constitutional amendments designed to rein in the federal government’s power.

The real threat to our constitutional rights today is posed not by an Article V convention of the states, but by an out-of-control federal government, exercising powers that it does not have and abusing powers that it does.

The federal government’s unrelenting encroachment upon the sovereign rights of the states and the individual rights of citizens, and the Supreme Court’s failure to prevent it, have led me to join the Legal Board of Reference for the Convention of States Project. The Project’s mission is to urge 34 state legislatures to call for an Article V convention limited to proposing constitutional amendments that “impose fiscal restraints on the federal government, limit its power and jurisdiction, and impose term limits on its officials and members of Congress.” I am joined in this effort by many well-known constitutional conservatives, including Mark Levin, Professor Randy Barnett, Professor Robert George, Michael Farris, Mark Meckler, Professor Robert Natelson, Andrew McCarthy, Professor John Eastman, Ambassador Boyden Gray, and Professor Nelson Lund. All of us have carefully studied the original meaning of Article V, and not one of us would support an Article V convention if we believed it would pose a significant threat to our Second Amendment rights or any of our constitutional freedoms. To the contrary, our mission is to reclaim our democratic and individual freedoms from an overreaching federal government.

—-

The Framers of our Constitution carefully limited the federal government’s powers by specifically enumerating those powers in Article I, and the states promptly ensured that the Constitution would expressly protect the “right of the people to keep and bear arms” by adopting the Second Amendment. But the Framers understood human nature, and they could foresee a day when the federal government would yield to the “encroaching spirit of power,” as James Madison put in the Federalist Papers, and would invade the sovereign domain of the states and infringe the rights of the citizens. The Framers also knew that the states would be powerless to remedy the federal government’s encroachments if the process of amending the Constitution could be initiated only by Congress; as Alexander Hamilton noted in the Federalist Papers, “the national government will always be disinclined to yield up any portion of the authority” it claims. So the Framers wisely equipped the states with the means of reclaiming their sovereign powers and protecting the rights of their citizens, even in the face of congressional opposition. Article V vests the states with unilateral power to convene for the purpose of proposing constitutional amendments and to control the amending process from beginning to end on all substantive matters.

—-

The Framers of our Constitution carefully limited the federal government’s powers by specifically enumerating those powers in Article I, and the states promptly ensured that the Constitution would expressly protect the “right of the people to keep and bear arms” by adopting the Second Amendment. But the Framers understood human nature, and they could foresee a day when the federal government would yield to the “encroaching spirit of power,” as James Madison put in the Federalist Papers, and would invade the sovereign domain of the states and infringe the rights of the citizens. The Framers also knew that the states would be powerless to remedy the federal government’s encroachments if the process of amending the Constitution could be initiated only by Congress; as Alexander Hamilton noted in the Federalist Papers, “the national government will always be disinclined to yield up any portion of the authority” it claims. So the Framers wisely equipped the states with the means of reclaiming their sovereign powers and protecting the rights of their citizens, even in the face of congressional opposition. Article V vests the states with unilateral power to convene for the purpose of proposing constitutional amendments and to control the amending process from beginning to end on all substantive matters.

The day foreseen by the Framers – the day when the federal government far exceeded the limits of its enumerated powers – arrived many years ago. The Framers took care in Article V to equip the people, acting through their state legislatures, with the power to put a stop to it. It is high time they used it.

Charles J. Cooper is a founding member and chairman of Cooper & Kirk, PLLC. Named by The National Law Journal as one of the 10 best civil litigators in Washington, he has over 35 years of legal experience in government and private practice, with several appearances before the United States Supreme Court and scores of other successful cases on both the trial and appellate levels.

Article 5 - How we have learned more and more about the Constitution’s “Convention for Proposing Amendments”

How We Have Learned More and More About the Constitution’s “Convention for Proposing Amendments”

Robert Natelson, Independence Institute’s Senior Fellow in Constitutional Jurisprudence and Head of the Institute’s Article V Information Center

This past week, conservative icon Phyllis Schlafly contributed a short piece to Townhall.com, in which she attacked the movement for an Article V convention. As I wrote in my response, she was relying on claims about the convention that had been superseded by modern research.

You can classify modern Article V writing in three broad waves. (There are many exceptions, but the generalization is valid, I think.) The first wave consisted of publications from the 1960s and 1970s, mostly — but not exclusively—by liberal academics who opposed conservative efforts to trigger a convention. Examples include articles by Yale’s Charles Black, William and Mary’s William Swindler, Duke’s Walter Dellinger, and Harvard’s Lawrence Tribe.

Typically, these authors concluded that an Article V “constitutional convention” (as they called it) could not be limited to a single subject. That, as we now know, was a mistake. A related error was their assumption that, when the Founders referred to a “general” convention, they meant a convention with unlimited subject matter. Actually, a “general convention” meant one in which all the states, or at least states from all regions, participated. It was the opposite of a “partial” or regional convention, and it had nothing to do with the scope of the subject matter.

The mistakes these authors made can be attributed partly to the agenda-driven nature of their writings, and their failure to examine many historical sources. They seldom ventured beyond The Federalist Papers and a few pages from the transcript of the 1787 Constitutional Convention.

Also in the First Wave was a 1973 study sponsored by the American Bar Association. The ABA document did conclude that a “constitutional convention” could be limited, but it was not a very solid piece of research, perhaps because (if my information is accurate) the principal writers were not professional scholars, but a pair of law students.

The Second Wave began in 1979 with a publication issued by President Carter’s U.S. Office of Legal Counsel and written by attorney John Harmon. For its time, it was a particularly thorough job. Among the other authors in this wave were Grover Rees III and the University of Minnesota’s Michael Stokes Paulsen. The most elaborate publication of this era was by Russell Caplan, whose book, Constitutional Brinksmanship, was released by Oxford University Press in 1988.

Second Wave authors accessed far more material than their predecessors. They paid more attention to the 1787–90 ratification debates. Caplan even made some reference to earlier interstate conventions. Most of them (Paulsen was an exception) correctly concluded that an Article V gathering could be limited.

But Second Wave writers did make some mistakes. They continued to refer to an Article V conclave as a “constitutional convention.” Some of them assumed, as some First Wave writers had, that Congress had broad authority under the Necessary and Proper Clause to regulate the convention and the selection and apportionment of delegates. None investigated the records of other interstate conventions in detail, or fully grasped their significance.

The Third Wave began in the 21st century. Its contributing authors include the University of San Diego’s Michael Rappaport, former House of Representatives Senior Counsel Mike Stern, the Goldwater Institute’s Nick Dranias, and myself. We have been able to place the Article V convention into its larger legal and historical context.

Like most of the Second Wave writers, we understand that an Article V convention can be limited. But we also have learned a lot of other things: The gathering is not a constitutional convention, it was modeled after a long tradition of limited-purpose gatherings, and it is governed by a rich history of practice and case law.

We also know that the Necessary and Proper Clause does not apply to conventions. That clause gives Congress power to make laws to carry into execution certain enumerated powers and “all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof.” But a convention for proposing amendments is not part of the “Government of the United States,” nor is it a “Department or Officer thereof.” Supreme Court precedent, as well as the wording of the Constitution, make this clear. For this and other reasons, congressional powers over the process are quite limited.

A few days ago, a friend sent me a 1987 report issued by the U.S. Justice Department. The title is “Limited Constitutional Conventions Under Article V of the United States Constitution.” As the date would suggest, this is a typical Second Wave publication. In addition to labeling an Article V Convention as a “constitutional convention,” it also assumes that a “general” convention is one that is unlimited as to subject matter. It shows no familiarity with any previous1787interstate conventions other than the gathering. It makes the erroneous assumption that the latter meeting was called by Congress under the Articles of Confederation. It fails to under-stand the nature of the convention as a meeting of commissioners from state legislatures. It asserts erroneously that all 19th century state applications were for an unlimited convention. (In fact, several were limited.) And it makes the inaccurate assumption that Congress has power under the Necessary and Proper Clause to prescribe procedures for an amendments convention.

Such documents are of historical interest, but they should no longer be taken as authoritative.

Article 6 - How the Courts have clarified the Constitution’s Amendment Process

How the Courts have Clarified the Constitution’s Amendment Process

Robert Natelson, Independence Institute’s Senior Fellow in Constitutional Jurisprudence and Head of the Institute’s Article V Information Center

One source of security we have in using the Constitution’s amendment process is the courts’ (including the U.S. Supreme Court) long history of protecting the integrity of the procedure.

Many of those who pontificate on the subject are largely unaware of this jurisprudence. As a result, they often debate questions that the courts have long resolved or promote scenarios (such as the “runaway” scenario) that the law has long foreclosed.

Here are some of the key issues the courts have addressed, either in binding judgments or in what lawyers call “persuasive authority.” This listing of cases is only partial.

- Article V grants enumerated powers to named assemblies—that is, to Congress, state legislatures, conventions for proposing amendments, and state conventions. When an assembly acts under Article V, that assembly executes a “federal function” different from whatever other responsibilities it may have. Hawke v. Smith, 253U.S.221 (1920); Leser v. Garnett, 258 U.S. 130 (1922); State ex rel. Donnelly v. Myers, 127Ohio St.104, 186 N.E. 918 (1933); Dyer v. Blair,390 F. Supp. 1291 (N.D. Ill. 1975) (Justice Stevens).

- Article V gives authority to named assemblies, without participation by the executive. Hollingsworth v. Virginia, 3 U.S. (3 Dall.) 378 (1798).

- Where the language of Article V is clear, it must be enforced as written. UnitedStates v. Sprague, 282U.S.716 (1931).

- That does not mean, as some have claimed, that judges may never go beyond reading the words and guessing what they signify. Rather, a court may consider the history underlying Article V. Dyer v. Blair, 390F. Supp.1291(N.D. Ill.1975) (Justice Stevens). It may also consider what is implied as well as what is expressed. Dillon v. Gloss,256 U.S. 368 (1921). In other words, courts apply the same rules of interpretation to Article V as elsewhere.

- Just as other enumerated powers in the Constitution bring with them certain incidental authority, so also do the powers enumerated in Article V. State ex rel.Donnelly v. Myers, 127Ohio St.104, 186N.E. 918 (1933). This point and the one previous are important in determining the scope of such Article V words as “call,” “convention,” and “application.”

- The two - thirds vote required in Congress for proposing amendments is two thirds of a quorum present and voting, not of the entire membership. State of Rhode Island v. Palmer, 253 U.S. 320 (1920).

- A convention for proposing amendments is, like all of its predecessors, a “convention of the states.” Smith v. UnionBank, 30 U.S. 518, 528 (1831). The national government is not concerned with how Article V conventions or state legislatures are constituted. United States v.Thibault,47 F.2d169(2d Cir.1931).

- No legislature or convention has power to alter the ratification procedure. That is fixed by Article V. Hawke v. Smith,253U.S. 221 (1920);United States v. Sprague, 282 U.S. 716 (1931). Some “runaway”alarmists have suggested that a convention for proposing amendments could decree ratification by national referendum, but the Supreme Court has ruled this out. Dodgev. Woolsey,59 U.S. 331 (1855). Neithercan a state mutate its own ratifying procedure into a referendum. State of RhodeIsland v. Palmer, 253 U.S. 320 (1920).

- Congress may not try to manipulate the ratification procedure, other than by choosing one of two specified “modes of ratification.” Idaho v. Freeman,529 F. Supp. 1107 (D. Idaho 1981), a judgment vacated as moot by Carmen v. Idaho, 459 U.S. 809 (1982); compareUnited Statesv. Sprague, 282 U.S. 716 (1931).

- A convention meeting under Article V may be limited to its purpose. In ReOpinion of the Justices, 204 N.C. 306, 172 S.E. 474 (1933).

- But an outside body may not dictate an Article V assembly’s rules and procedures. Leser v. Garnett, 258 U.S. 130 (1922); Dyer v. Blair, 390F. Supp.1291(N.D. Ill.1975) (Justice Stevens).

- Nor may the assembly be compelled to resolve the issue presented to it in a particular way. State ex rel. Harper v. Waltermire,691P.2d826(1984); AFL-CIO v. Eu, 686P.2d609(Cal.1984); Miller v. Moore, 169F.3d1119(8th Cir.1999); Gralike v. Cook, 191F.3d911, 924-25 (8thCir. 1999), affirmed on other grounds sub nom. Cook v. Gralike,531 U.S. 510 (2001); Barker v. Hazeltine, 3F. Supp. 2d1088,1094 (D.S.D. 1998);League of Women Voters of Maine v. Gwadosky,966F. Supp.52 (D. Me. 1997);Donovan v. Priest, 931 S.W.2d 119 (Ark. 1996).

- Article V functions are complete when a convention or legislature has acted. There is no need for other officials to pro-claim the action. United States ex rel. Widenmann v. Colby, 265 F.398(D.C. Cir. 1920), affirmed 257 U.S. 619 (1921).

As these cases illustrate, the courts are very much in the business of protecting Article V procedures, and they have done so for more than two centuries.

Article 7 - The Myth of a Runaway Amendments Convention

The Myth of a Runaway Amendments Convention

Robert Natelson, Independence Institute’s Senior Fellow in Constitutional Jurisprudence and Head of the Institute’s Article V Information Center

The Founders bequeathed to Americans a method to bypass the federal government and amend the Constitution, empowering two-thirds of the states to call an amendments convention. In the wake of Mark Levin’s bestselling book, The Liberty Amendments, proposing just such a convention, some have raised entirely unnecessary alarms. Surprisingly, a few of the leading lights of conservatism have been among the alarmists. But their concerns are based on an incomplete reading of history and judicial case law.

Phyllis Schlafly is a great American and a great leader, but her speculations about the nature of the Constitution’s “convention for proposing amendments” are nearly as quaint as Dante’s speculations about the solar system. Those speculations simply overlook the last three decades of research into the background and subsequent history of the Constitution’s amendment process. They also ignore how that process actually works, and how the courts elucidate it.

Article V of the Constitution provides for a “convention for proposing amendments.” The Founders inserted this provision to enable the people, acting through their state legislatures, to rein in an abusive or runaway federal government. In other words, the Founders created the convention for precisely the kind of situation we face now.

Mrs. Schlafly doesn’t think we know much else about the process. She writes, “Everything else about how an Article V Convention would function, including its agenda, is anybody’s guess.”

But she’s wrong. There is no need to guess. There is a great deal we know about the subject.

The “convention for proposing amendments” was consciously modeled on federal conventions held during the century leading up to the Constitutional Convention. During this period the states — and before Independence, the colonies — met together on average about every 40 months. These were meetings of separate governments, and their protocols were based on international practice. Those protocols were well-established and are inherent in Article V.

Each federal convention has been called to address one or more discrete, prescribed problems. A convention “call” cannot determine how many delegates (“commissioners”) each state sends or how they are chosen. That is a matter for each state legislature to decide.

A convention for proposing amendments is a meeting of sovereignties or semi-sovereignties, and each state has one vote. Each state com-missioner is empowered and instructed by his or her state legislature or its designee.

As was true of earlier interstate gatherings, the convention for proposing amendments is called to propose solutions to discrete, preassigned problems. There is no record of any federal convention significantly exceeding its preassigned mandate — not even the Constitutional Convention, despite erroneous claims to the contrary.

The state legislatures’ applications fix the subject-matter for a convention for proposing amendments. When two-thirds of the states apply on a given subject, Congress must call the convention. However, the congressional call is limited to the time and place of meeting, and to reciting the state-determined subject.

In the unlikely event that the convention strays from its prescribed agenda (and the commissioners escape recall), any “proposal” they issue is ultra vires (“beyond powers”) and void. Congress may not choose a “mode of ratification” for that proposal, and the necessary three-quarters of the states would not ratify it in any event.

Contrary to Mrs. Schlafly’s claim that “Article V doesn’t give any power to the courts to correct what does or does not happen,” the courts can and do adjudicate Article V cases. There has been a long line of those cases from 1798 into the 21st century.

“But,” you might ask, “Will the prescribed convention procedures actually work?“

They already have. In 1861, in an effort to prevent the Civil War, the Virginia legislature called for an interstate gathering formally entitled the Washington Conference Convention and, informally, the Washington Peace Conference. The idea was that the convention would draft and propose one or more constitutional amendments that, if ratified, would weaken extremists in both the North and the South, and thereby save the Union. This gathering differed from an Article V convention primarily in that it made its proposal to Congress rather than to the states. In virtually every other respect, however, it was a blueprint for an Article V convention.

When the convention met in Washington, D.C., on February 4, 1861, seven states already had seceded. Of the 26 then remaining in the Union, 21 sent committees (delegations). The conference lasted until February 27, when it proposed a 7-section constitutional amendment.

The assembly followed to the letter the convention rules established during the 18th century—the same rules relied on by the Constitution’s Framers when they provided for a Convention for Proposing Amendments. Specifically:

- The convention call fixed the place, time, and topic, but did not try to dictate other matters, such as selection of commissioners (delegates) or convention rules.

- At the convention, voting was by state. One vote was, apparently inadvertently, taken per capita, but that was quickly corrected.

- The committee from each state was selected in the manner that state’s legislature directed.

- The conclave adopted its own rules and selected its own officers. Former President John Tyler served as president.

- The commissioners stayed on topic. One commissioner made a motion that was arguably off topic (changing the President’s term of office), but that was voted down without debate.

Congress subsequently deadlocked over the amendment, but the convention itself did everything right: It followed all the protocols listed above, and it produced a compromise amendment. Although the convention met in a time of enormous stress, this “dry run” came off well, with none of Mrs. Schlafly’s speculative “horribles.”

In any political procedure, there are always uncertainties, but in this case they are far fewer than predicted by anti-convention alarmists. And they must be balanced against a certainty: Unless we use the procedure the Founders gave us to rein in a runaway Congress, then Congress will surely continue to run away.

Article 8 - Already Adopted a Balance Budget Amendment

Why a State Should Adopt an Article V Application for A Convention of States if It Has Already Adopted a Balanced Budget Amendment Application

By Michael Farris, JD, LLM

Article V provides two methods to pro-pose constitutional amendments—one controlled by Congress and one con-trolled by the state legislatures. In the last two years, there has been a significant renewal of interest in employing the state-based method for proposing amendments to the Constitution. This newfound interest in Article V arises largely from the belief that the Congress will never propose amendments that impose meaningful restrictions on federal power.

There are only two “Article V” movements that have made significant progress: the Balanced Budget Amendment and the Convention of States Project. The first (BBA) seeks one single amendment requiring the federal government to adopt a balanced budget. The second (COS) seeks broad limitations on federal power—specifically, “imposing fiscal restraints on the federal government, limiting the power and jurisdiction of the federal government, and imposing term limits on federal officials.”

The COS Project was launched in the fall of 2013, and in its first year secured passage of a formal application from the legislatures of Georgia, Florida, and Alaska.

The BBA project has been underway for over forty years and has secured a variety of applications in a great number of states. However, determining the current number of states that have a valid, pending BBA application presents a challenge. Two issues make counting difficult. First, there is significant variance among the language of the various BBA applications, which raises potential problems with aggregation. Second, many states have rescinded their prior BBA applications. We will discuss these legal issues below in Section 4.

The COS Project is working to pass applications with identical operative language in 34 states. This ensures that no issues of aggregation can arise. Moreover, no states have rescinded a COS application.

There are at least five significant reasons why a state legislature should adopt a COS application even if it has already adopted a valid BBA application.

1.There is no rule against a state passing two or more applications.

Every Article V application from a state legislature must identify its purpose. There have been over 400 applications in the history of the Republic, and yet there has never been an Article V Convention because two-thirds of the states have never agreed on the subject matter. There have been countless occasions when a state has passed a second or third application for a Convention on a different topic, even while a prior application was still pending.

This historical practice reflects common sense. There may be multiple issues that states want to see addressed through a constitutional amendment. And the process of building a coalition of 34 states is sufficiently daunting that the states see the wisdom in supporting multiple efforts that use varying approaches to accomplish their goals.

2. Only the COS application seeks to restore federalism.

The BBA seeks to prohibit the federal government from taking the nation even deeper into debt. This is, of course, a worthy goal, and one that COS supports. However, we also seek to address the root cause of the problem. The root cause of debt is excessive federal spending. And the cause of excessive spending is, at least in significant part, entitlement and other domes-tic programs that are within the exclusive jurisdiction of the states under the original meaning of the Constitution.

By 2020, 89% of the federal budget will need to be devoted to just four items: interest on the national debt, Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security. This is untenable and leaves our nation’s infra-structure and defense at great risk. A BBA alone will not cure this problem. We must restrict Congress’ virtually unlimited power to spend.

In the Obamacare decision, Chief Justice Roberts’ majority ruling held that there is no constitutional limitation on the power of Congress to tax and spend. This is the core problem. And, we must fix it. This means a return to the states of exclusive jurisdiction for several areas of government expenditure.

Not only has Congress invaded the province of the states with regard to domestic spending, it has increasingly taken charge of state governments by means of conditional federal grants. Congress coerces the states to do its bidding by taking money from taxpayers (current or future), and then offering federal funding for mandated programs.

This leaves the state legislatures in the structural position of being unable to achieve their central mission—representing the voters of their own states. Rather, state legislators are effectively required to do the will of Congress. This is a clear violation of the principles of a Republican form of government.

Regaining true federalism is not just a matter of insisting on adherence to the original meaning of the Constitution. If freedom is to survive, we must return to the structural designs of a robust federalism, with a truly limited federal government. Only the COS seeks to address this core issue.

3.There are other structural issues with the federal government that require immediate attention.

Article I, Section1 of the Constitution commands that all federal laws must be made by Congress. But the Executive Branch, through both executive orders and bureaucratic regulations, makes an ever- escalating percentage of the federal laws that are crippling our economy. This problem is persistent regard-less of which political party controls the White House.

The Supreme Court has, on approximately thirty occasions, acknowledged that the only limitation on its power is the Court’s own sense of self-restraint. We must apply appropriate checks and balances to the Supreme Court.

We see the State Department and many in the United States Senate increasingly enamored with the idea that international law should govern the domestic policy of the United States. Under the Supremacy Clause, all state laws and state constitutions must yield to any ratified international treaty. We need to limit the treaty power to the international sphere and not allow it to invade the domestic authority of the states. The chief reasons for the growth of the federal government involve misuse of the General Welfare Clause and the Commerce Clause. Both of these need to be returned to their original meaning. We need to have a serious discussion on the issue of term limits for members of Congress and the federal judiciary. (For example, federal judges could be limited to one eight-year term without reappointment. A single term would continue to guarantee judicial independence without creating a sense of permanent judicial supremacy.)

All of these issues can be effectively addressed under the language of the model COS application. None of these issues can be addressed under the BBA application.

4. The COS Project avoids legal issues presented by the BBA which will likely result in lengthy delays.

At one time or another,34 state legislatures have applied for a BBA convention. However, 10 of these applications have since been rescinded. Moreover, there is considerable variation in the language of BBA applications. Consider some examples:

The 2014 application from Ohio calls for a convention limited to “proposing an amendment to the United States Constitution requiring that in the absence of a national emergency the total of all federal appropriations made by the Congress for any fiscal year may not exceed the total of all estimated federal revenues for that fiscal year, together with any related and appropriate fiscal restraints.”

On the other hand, the current Maryland application calls for a convention to propose a specific amendment, providing that “The total of all Federal appropriations made by the Congress for any fiscal year may not exceed the total of the estimated Federal revenues for that fiscal year, excluding any revenues derived from borrowing; and this prohibition extends to all Federal appropriations and all estimated Federal revenues, excluding any revenues derived from borrowing.” It goes on to specify circumstances under which the requirement could be suspended.

Mississippi’s application also calls for the proposal of a specifically-worded amendment, but its language is different from Maryland’s proposal. Mississippi’s language would prohibit congressional appropriations that would exceed revenues in a given fiscal year, but also requires that the national debt be repaid within a specified timeline at a specified rate, etc.

Still other states’ resolutions for a BBA demonstrate additional variations on the theme.

This raises a very serious concern about aggregation. While Congress has a very limited role in the state-initiated process of proposing amendments, legislative practice and the text of Article V suggest that Congress determines when 34 states have applied for a convention on the same subject.

The reality is that if the state applications are not uniform or essentially uni-form (as to their operative language), Congress will be entitled to make a political judgment about whether the applications should be aggregated. If there is a simple majority in both houses of Congress that favor an Article V Convention to consider a BBA, then Congress will likely grant a great deal of latitude on the issue of aggregation. However, if a majority of either house of Congress is opposed to either the idea of a Balanced Budget Amendment or the convening of an Article V Convention in general, Congress would “interpret” the applications very narrowly and conclude that 34 states have not applied for a convention on the same subject.

Regardless of which way the vote goes, litigation will certainly follow to test the question of aggregation. And while good substantive arguments can be made to bolster the notion that aggregation should be broadly accepted rather than narrowly confined, the courts would likely avoid deciding this question.

In fact, it is very likely that the Supreme Court will take the position that the question of aggregation is a political question whenever the state applications are not identical or essentially identical as to their operative language. Litigation on this point would add two to four years to the process of calling a BBA convention, because the legal issues will be viewed as important and sufficiently close to merit full consideration.

In short, litigation will prolong the process, and whatever Congress decides on the BBA aggregation issue is likely to be affirmed in the courts. The Convention of States Project avoids this problem altogether. Our strategy is for 34 states to commit to adopting our model language for the operative portion of their applications, thus precluding any legitimate question about aggregation. Congress will have no cause to make a political judgment, and the courts will enforce the direct language of Article V forcefully upon such facts.

5. Our nation doesn’t have time to wait and see what will happen with a BBA before it tackles the issues raised by the COS.

The problems our nation faces are complex and urgent. If we are going to preserve liberty, restore self-governance and prevent an economic collapse, we must act promptly.

Under the best case scenario for the BBA, sufficient applications will be amassed in 2016. If we add just two years for litigation, we will be at 2018 before a convention could be held. Then there will be the ratification fight that will surely last until 2020.

The critical issues that we can address through COS cannot safely be delayed until 2020.

Since there is no barrier to prevent a state from passing both a BBA and COS, there is every reason to proceed with both applications as quickly as possible in as many states as possible.

State Applications for Article V Convention to Propose a Balanced Budget Amendment

| DATE | STILL | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| STATE | PASSED | OPERATIVE LANGUAGE | PENDING |

| Alabama | 6-1-11 | “for the specific and exclusive purpose of proposing an amendment to that Constitution requiring that, in the absence of a national emergency . . . the total of all federal appropriations made by Congress for any fiscal year not exceed the total revenue for that fiscal year.” | Yes |

| Alaska | 2-24-82 | “for the sole and exclusive purpose of proposing an amendment to the Constitution of the United States which would require that, In the absence of a national emergency, the total of all appropriations made by Congress for a fiscal year shall not exceed the total of all estimated federal revenues for that fiscal year.” | Yes |

| Arizona | Rescinded | No | |

| Arkansas | 3-5-79 | “for the specific and exclusive purpose of proposing an amendment to the Federal Constitution federal revenues for that fiscal year.” requiring in the absence of a national emergency that the total of all Federal appropriations made by the Congress for any fiscal year may not exceed the total of all estimated Federal revenues for that ficsal[sic] year.” | Yes |

| Colorado | 4-5-78 | “for the specific and exclusive purpose of proposing an amendment to the federal constitution prohibiting deficit spending except under conditions specified in such amendment.” | Yes |

| Delaware | 2-25-76 | “for the purpose of proposing of the following amendment to the Constitution of the United States: 'ARTICLE The costs of operating the Federal Government shall not exceed its income during any fiscal year, except in the event of declared war.'” | Yes |

| Florida | 4-21-14 | “limited to proposing an amendment to the Constitution requiring that, in the absence of a national emergency, the total of all federal appropriations made by the Congress for any fiscal year may not exceed the total of all estimated federal revenues for that fiscal year, together with any related and appropriate fiscal restraints.” | Yes |

| Georgia | 2-20-14 | “limited to consideration and proposal of an amendment requiring that in the absence of a national emergency the total of all federal appropriations made by the Congress for any fiscal year may not exceed the total of all estimated federal revenues for that fiscal year.” | Yes |

| Idaho | Rescinded | No | |

| Indiana | 3-12-57 | “for proposing the following article as an amendment to the Constitution of the United States: 'ARTICLE “'SECTION 1. On or before the 15th day after the beginning of each regular session of the Congress, the President shall transmit to the Congress a budget which shall set forth his estimates of the receipts of the Government, other than trust funds, during the ensuing fiscal year under the laws then existing and his recommendations with respect to expenditures to be made from funds other than trust funds during such ensuing fiscal year, which shall not exceed such estimate of receipts. If the Congress shall authorize expenditures to be made during such ensuing fiscal year in excess of such estimated receipts, it shall not adjourn for more than 3 days at a time until action has been taken necessary to balance the budget for such ensuing fiscal year. In case of war or other grave national emergency, if the President shall so recommend, the Congress by a vote of three-fourths of all the Members of each House may suspend the foregoing provisions for balancing the budget for periods, either successive or otherwise, not exceeding 1 year each.” to the effect that, in the absence of a national emergency, the total of all Federal appropriations made by the Congress for any fiscal year may not exceed the total of all estimated Federal revenues for that fiscal year.” | Yes |

| Iowa | 7-1-80 | “for the specific and exclusive purpose of proposing an amendment to the Constitution of the United States to require a balanced federal budget and to make certain exceptions with respect thereto.” | Yes |

| Kansas | 2-8-79 | “for the sole and exclusive purpose of proposing an amendment to the Constitution of the United States which would require that, in the absence of a national emergency, the total of all appropriations made by the Congress for a fiscal year shall not exceed the total of all estimated federal revenues for such fiscal year.” | Yes |

| Louisiana | 5-14-14 | “for the specific and exclusive purpose of proposing an amendment to the Constitution of the United States, for submission to the states for ratification, to require that in the absence of a national emergency the total of all federal outlays made by congress for any fiscal year may not exceed the total of all estimated federal revenues for that fiscal year, together with any related and appropriate fiscal restraints.” | Yes |

| Maryland | 1-28-77 | “for the specific and exclusive purpose of proposing [Article XXVII] . . . PROPOSED ARTICLE XXVII: “The total of all Federal appropriations made by the Congress for any fiscal year may not exceed the total of the estimated Federal revenues for that fiscal year, excluding any revenues derived from borrowing; and this prohibition extends to all Federal appropriations and all estimated Federal revenues, excluding any revenues derived from borrowing. The President in submitting budgetary requests and the Congress in enacting appropriation bills shall comply with this Article. If the President proclaims a national emergency, suspending the requirement that the total.of all Federal appropriations not exceed the total estimated Federal revenues for a fiscal year, excluding any revenues derived from borrowing, and two-thirds of all Members elected to each House of' the Congress so determined by Joint Resolution, the total of all Federal appropriations may exceed the total estimated Federal revenues for that fiscal year.” | Yes |

| Michigan | 3-26-14 | “limited to proposing an amendment to the constitution of the United States requiring that in the absence of a national emergency, including, but not limited to, an attack by a foreign nation or terrorist organization within the United States of America, the total of all federal appropriations made by the congress for any fiscal year may not exceed the total of all estimated federal revenues for that fiscal year, together with any related and appropriate fiscal restraints.” | Yes |

| Mississippi | 4-29-75 | “for the proposing of the following amendment to the Constitution of the United States: 'Article ”'Section 1. Except as provided in Section 3, the Congress shall make no appropriation for any fiscal year if the resulting total of appropriations for such fiscal year would exceed the total revenues of the United States for such fiscal year. “'Section 2. There shall be no increase in the national debt and such debt, as it exists on the date on which this article is ratified, shall be repaid during the one-hundred-year period beginning with the first fiscal year which begins after the date on, which this article is ratified. The rate of repayment shall be such that one-tenth (1/10) of such debt shall be repaid during each ten-year interval of such one-hundred-year period. ”'Section 3. In time of war or national emergency, as declared by the Congress, the application of Section 1 or Section 2 of this article, or both such sections, may be suspended by a concurrent resolution which has passed the Senate and the House of Representatives by an affirmative vote of three-fourths (3/4) of the authorized membership of each such house. Such suspension shall not be effective past the two-year term of the Congress which passes such resolution, and if war or an emergency continues to exist such suspension, must be reenacted in the same manner as provided herein. “'Section 4. This article shall apply only with respect to fiscal years which begin more than, six (6) months after the date on which this article is ratified.'” | Yes |

| Missouri | 7-21-83 | “for the specific and exclusive purpose of proposing an amendment to the Constitution of the United States to require a balanced federal budget and to make certain exceptions with respect thereto;” | Yes |

| Nebraska | 2-8-79 | “for the specific and exclusive purpose of proposing an amendment to the Constitution of the United States requiring in the absence of a national emergency that the total of all federal appropriations made by the Congress for any fiscal year may not exceed the total of all estimated federal revenue for that fiscal year.” | Yes |

| Nevada | 2-8-79 | “for the purpose of proposing an amendment to the United States Constitution which would require that, in the absence of a national emergency, the total of the appropriation made by the Congress for each fiscal year may not exceed the total of the estimated federal revenues for that year;” | Yes |

| New Hampshire | 5-16-12 | “for the specific and exclusive purpose of proposing an amendment to the Constitution of the United States, for submission to the states for ratification, requiring, with certain exceptions, that for each fiscal year the president of the United States submit and the Congress of the United States adopt a balanced federal budget;” | Yes |

| New Mexico | 2-8-79 | “for the specific and exclusive purpose of proposing an amendment to the constitution requiring in the absence of a national emergency that the total of all federal appropriations made by the congress for any fiscal year may not exceed the total of all estimated federal revenues for that fiscal year;” | Yes |

| North Carolina | 1-29-79 | “for the exclusive purpose of proposing an amendment to the Constitution of the United States to require a balanced federal budget in the absence of a national emergency.” | Yes |

| North Dakota | Rescinded | No | |

| Ohio | 2014 | “limited to proposing an amendment to the United States Constitution requiring that in the absence of a national emergency the total of all federal appropriations made by the Congress for any fiscal year may not exceed the total of all estimated federal revenues for that fiscal year, together with any related and appropriate fiscal restraints;” | Yes |

| Oklahoma | Rescinded | No | |

| Oregon | Rescinded | No | |

| Pennsylvania | 2-8-79 | “for the specific and exclusive purpose of proposing an amendment to the Federal Constitution requiring in the absence of a national emergency that the total of all Federal appropriations made by the Congress for any fiscal year may not exceed the total of all estimated Federal revenues for that fiscal year;” | Yes |

| South Carolina | Rescinded | No | |

| South Dakota | Rescinded | No | |

| Tennessee | 3-10-14 | “limited to proposing an amendment to the Constitution of the United States requiring that in the absence of a national emergency the total of all Federal appropriations made by the Congress for any fiscal year may not exceed the total of all estimated Federal revenues for that fiscal year, together with any related and appropriate fiscal restraints.” | Yes |

| Texas | 3-15-79 | “for the specific and exclusive purpose of proposing an amendment to the federal constitution requiring in the absence of a national emergency that the total of all federal appropriations made by the congress for any fiscal year may not exceed the total of all estimated federal revenues for that fiscal year;” | Yes |

| Utah | Rescinded | No | |

| Virginia | Rescinded | No | |

| Wyoming | Rescinded | No |

Article 9 - Let’s provide our children with common sense, not common core

Let’s Provide Our Children Common Sense, Not Common Core

Michael P. Farris, JD, LLM, Convention of States Action — Senior Fellow for Constitutional Studies

We are often reminded that Common Core is a “voluntary” program, and that states still retain complete control over their public educational curriculum. But the truth is, until the states wrest control over education from the clutches of the federal government, there will be grave consequences for states that refuse to acquiesce.

In 2014, for instance, the U.S. Department of Education denied Oklahoma’s request for a waiver from No Child Left Behind—a thinly veiled, politically motivated punishment for the state’s rejection of the “voluntary” Common Core program.

State legislators who believe that the best decisions about public education are the ones made closest to home should plan and implement a meaningful, strategic response to this kind of federal bullying.

But what does that look like?

A lawsuit against the feds would be an up-hill battle. At most, it could win on a narrow, procedural basis. Alternatively, the states could use this moment to take a historic step toward dismantling the basis for illicit federal power grabs.

The Constitution’s Framers believed that having the right structure for decision-making was essential for the preservation of liberty. They had learned this lesson in the crucible of a very real conflict.

Our Founders had refused to pay the taxes imposed by Parliament, insisting upon their rights under British law to be subject only to taxes imposed by their own elected representatives. They stood up for the principle of self-government — and the victory they won stands as the

crowning achievement of that generation. Today, this educational conflict over Common Core, an outrage to parents across the nation, reveals that we’ve drifted far off course.

The principle of “enumerated powers” means that the federal government has no authority to dictate the educational policy of any state, directly or indirectly, because it wasn’t given this power under the Constitution. Yet states like Oklahoma are engaged in this battle because of the de facto collusion between the Supreme Court and Congress to gradually increase federal power.

While the Supreme Court has recognized that the federal government can’t directly regulate education, the court also has ruled that Congress’ power to tax and spend under the General Welfare Clause is, for most practical purposes, unlimited. Congress is therefore free to take money from a state’s taxpayers, then offer it back—on the condition that the state gives Congress control of its schools.

The Common Core battle also raises the fundamental issue of who makes federal law. The Founders thought they’d settled the question, declaring in Article I, Section 1 that all federal laws must be made by Congress. Yet states like Oklahoma are punished for challenging mere administrative decisions of the Obama administration.

What can you do?

Article V of the Constitution gives state legislatures the means to unilaterally pro-pose amendments to the Constitution that can remedy these modern perversions of our federal system.

The legislatures of Georgia, Florida, Alaska, and Alabama have already passed resolutions calling for a Convention of States under Article V, for the express purpose of proposing amendments to rein in a runaway federal government. This kind of specific, systemic correction is needed to repair the damaged structures of the Constitution and restore limitations on federal power.

You can help these other states in leading the way to real reform. When 34 states call for an amendments convention to re-strain the federal government, we will have our only realistic opportunity to reject not only Common Core, but all forms of illicit federal mandates.

Ultimately, this fight isn’t merely about education policy. It’s about the principle of self-government that is the real common core of America.

Article 10 - Final Constitutional Option

The Final Constitutional Option

Bob Berry

Having been dormant for centuries, a potent section in the U.S. Constitution is now in the minds and on the lips of a new generation of reformers who are determined to keep the nation out of an abyss. As America stares hard at the darkness ahead, the new reformers — supporters of The Convention of States Project — have begun to popularize this for-gotten constitutional provision that might well become Official Washington’s undoing.

The problem, which hardly needs stating, is that the federal government has become the very monster the Founders anticipated. Quite likely, the beast we face is far beyond anything that could have been imagined by the founding generation. Even today it is hard to adequately comprehend the omnipresent and, thanks to the NSA, omniscient federal menace that hangs over every aspect of life in 21st-century America.

The Founders’ concern that power would be consolidated at the federal level is dealt with in Article V of the U.S. Constitution.

Author Mark Levin, in his blockbuster best-seller, The Liberty Amendments: Restoring the American Republic, based his ideas for reform on this less well-known means by which amendments may be proposed — a process that entirely outflanks Washington’s fixed fortifications. Levin cogently argues that attempts at reform from within Washington are futile.

Obviously, what is needed is a way to trump the Beltway ruling class from without.

Enter Article V, which prescribes the amendment process. Article V establishes the amendment process as a two-phase affair: proposal, followed by ratification of three-fourths of the states. The states have no way to ratify that which has not first been proposed. From the beginning, the states have re-lied on congressional super-majorities to do the proposing.

But the Founders knew that Congress would be loath to propose anything that would limit federal power, so they included a way for the states to propose amendments in an ad hoc assembly that Article V styles as “A Convention for Proposing Amendments.”

The idea of using the amendments convention assembly has surfaced from time to time in U.S. history — most recently in the 1980s, with the movement to propose a Balanced Budget Amendment (BBA). The effort peaked with 33 states passing resolutions — just one shy of the required two-thirds of state legislatures, which would have compelled Congress to issue a call for the amendments convention.

That’s when the effort took a bizarre detour — into oblivion.

The BBA advocates of the 1980s, including then-President Reagan, were decidedly of the political right. The last thing anyone in the movement expected was for “friendlies” from elsewhere on the right to object to the idea in near hysterics as a plot to render the Constitution null and void. The unlikely opponents, while not necessarily opposed to a BBA, condemned in no uncertain terms the use of the amendments convention to propose it. It quickly became evident, from the critics’ rhetoric, that they had confused the Convention for Proposing Amendments assembly with a so-called plenary (full authority) Constitutional Convention.

BBA advocates attempted to clarify the difference between the types of conventions by pointing out that, as sovereigns, the states have never needed permission from the Constitution to call an actual Constitutional Convention. Indeed, the only reason to invoke Article V would be to self-limit the convention’s authority to “proposing amendments,” as the assembly’s name indicates.

The critics would have none of it.

In appeals to the public, the critics insidiously left out any mention of the ratification process by three-fourths of the states — the implication being that once the proceedings began, there would be nothing that could be done to hold it back when, inevitably, extreme elements moved to dissolve the Constitution. When challenged on this, the foes weaved the assertion into their conspiracy theory that the out-of-control assembly would simply declare its own sovereignty and dispense with the ratification process altogether!

As preposterous as this notion was, the accompanying slogan was more effective: “We don’t need a new Constitution!” Gobsmacked, the BBA proponents could only look on as state legislators made for the tall grass. One by one, states began rescinding BBA resolutions.

As a postscript to this sad chapter, it should be noted that by the late 1980s, the national debt had just topped $2 trillion. An effective BBA at that time could have stopped the bleeding that, by any objective measure, has become an existential threat.

The Professor

In 2009, an academic from the University of Montana was surveying opportunities for re-search. Of particular interest to Professor Robert G. Natelson were areas of constitutional scholarship characterized by a scarcity of research, poor research, or, optimally, both.

Intrigued by the vestigial Convention for Proposing Amendments mentioned in Article V, Natelson was struck by the paucity of modern-day scholarship on the topic, despite an abundance of original source material.

Quietly, he set to work.

Before long, Natelson had acquired nearly all of the journals of founding-era conventions. This was added to his existing collection of material from each state’s ratification convention as each considered whether or not to approve the proposed 1787 Constitution. A picture of early American convention tradition began to emerge.

Casting a wider net, he pulled in over 40 generally neglected Article V court decisions, some of which had been argued before the Supreme Court. In a series of publications, Natelson churned out his findings (available at www.articlevinfocenter.com), which surprised many — including himself.

The research quickly became the gold standard of scholarship about the process, known formally as the “State-Application-and-Convention” method of amending the Constitution.

Natelson held that, far from being a self-destruct mechanism, the Founders meant for the process to be used in parallel to the congressional method as yet another “check and balance” within the framework of the newly constituted federal government.

Most importantly, Natelson drew a strong distinction between the assembly mentioned in Article V and the oft-mentioned Constitutional Convention. For this reason, he is quick to correct anyone mistakenly referring to the Convention for Proposing Amendments as a “Constitutional Convention.”

Natelson’s research trove smashed the conspiracy theories of the 1980s and has become the intellectual base of the resurgent Article V movement that has been joined by Levin and other prominent reformers. When the history is written, it will record that this was the moment the Article V movement achieved critical mass.

The new reformers would do well to press on with the case for state-initiated amendments and ignore the tired conspiracy theories of the past. Having been marginalized to an almost comic degree, the foes of yesterday have been effectively dispatched.

When a battle is won, it is wise to move to the next battle, for the waiting opponent is formidable and lives on Capitol Hill.

Article 11 - Battle Over Coal

The Environmental Protection Agency’s Battle Over Coal is part of a larger War on Federalism.