This is an old revision of the document!

Table of Contents

All Surge Documents

Article 1-Solution As Big As Problem

A Solution As Big As The Problem

Michael P. Farris, JD, LLM, Convention of States Action — Senior Fellow for Constitutional Studies

We See Four Major Abuses Perpetrated by the Federal Government.

These abuses are not mere instances of bad policy. They are driving us towards an age of “soft tyranny” in which the government does not shatter men’s wills but “softens, bends, and guides” them. If we do nothing to halt these abuses, we run the risk of becoming nothing more than “a flock of timid and industrious animals, of which the government is the shepherd.”

(Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America,1840)

1. The Spending and Debt Crisis

The $17 trillion national debt is staggering, but it only tells part of the story. Under standard accounting practices, the federal government owes around $100 trillion more in vested Social Security benefits and other pro-grams. This is why the government cannot tax its way out of debt. Even if it confiscated everything, it would not cover the debt.

2. The Regulatory Crisis

The federal bureaucracy has placed a regulatory burden upon businesses that is complex, conflicted, and crushing. Little account-ability exists when agencies—rather than Congress—enact the real substance of the law. Research from the American Enterprise Institute shows that, since 1949, federal regulations have lowered the real GDP growth by 2% and made America 72% poorer.

3. Congressional Attacks on State Sovereignty

For years, Congress has been using federal grants to keep the states under its control. Combining these grants with federal mandates (which are rarely fully funded), Congress has turned state legislatures into their regional agencies rather than respecting them as truly independent republican governments.

A radical social agenda and an invasion of the rights of the people accompany all of this. While significant efforts have been made to combat this social erosion, these trends defy some of the most important principles.

4. Federal Takeover of the Decision-Making Process

The Founders believed that the structures of a limited government would provide the greatest protection of liberty. Not only were there to be checks and balances between the branches of the federal government, but power was to be shared between the states and federal government, with the latter only exercising those powers specifically granted in the Constitution.

Collusion among decision-makers in Washington, D.C., has replaced these checks and balances. The federal judiciary supports Congress and the White House in their ever-escalating attack upon the jurisdiction of the fifty states.

We need to realize that the structure of decision-making matters. Who decides what the law shall be is as important as what is decided. The protection of liberty requires a strict adherence to the principle that power is limited and delegated.

Washington, D.C., does not believe in this principle, as evidenced by an unbroken practice of expanding the boundaries of federal power. In a remarkably frank admission, the Supreme Court rebuffed a challenge to federal spending power, despite acknowledging that power had grown far beyond the bounds envisioned by the Founders.

What Does this Mean?

This is not a partisan issue. Washington, D.C., will never voluntarily relinquish meaningful power—no matter who is elected. The only rational conclusion is this: Unless some political force outside of Washington, D.C., intervenes, the federal government will continue to bankrupt this nation, embezzle the legitimate authority of the states, and destroy the liberty of the people. Rather than securing the blessings of liberty for future generations, Washington, D.C., is on a path that will enslave our children and grandchildren to the debts of the past. The problem is big, but we have a solution. Article V gives us a tool to fix the mess in D.C.

Our Solution Is Big Enough to Solve the Problem

Rather than calling a convention for a specific amendment, Convention of States Action (COSA) urges state legislatures to properly use Article V to call a convention for a particular subject—reducing the power of Washington, D.C. It is important to note that a convention for an individual amendment (e.g., a Balanced Budget Amendment) would be limited to that single idea. Requiring a balanced budget is a great idea that COSA fully supports. Congress, however, could comply with a Balanced Budget Amendment by simply raising taxes. We need spending restraints as well. We need restraints on taxation. We need prohibitions against improper federal regulation. We need to stop unfunded mandates.

A Convention of States needs to be called to ensure that we are able to debate and impose a complete package of restraints on the misuse of power by all branches of the federal government.

What Sorts of Amendments Could Be Passed?

The following are examples of amendment topics that could be discussed at a conven-tion of states:

- A Balanced Budget Amendment

- A redefinition of the General Welfare Clause (the original view was that the federal government could not spend money on any topic within the jurisdiction of the states)

- A redefinition of the Commerce Clause (the original view was that Congress was granted a narrow and exclusive power to regulate shipments across state lines–not all the economic activity of the nation)

- A prohibition on using international treaties and law to govern the domestic law of the United States

- A limitation on using executive orders and federal regulations to enact laws (since Congress is supposed to be the exclusive agency to enact laws)

- Imposing term limits on Congress and the Supreme Court

- Placing an upper limit on federal taxation

- Requiring the sunset of all existing federal taxes and a super-majority vote to replace them with new, fairer taxes

Of course, these are merely examples of what would be up for discussion. The Convention of States itself would deter-mine which ideas deserve serious consideration, and it would take a majority of votes from the states to formally pro-pose any amendments.

The Founders gave us a legitimate path to save our liberty by using our state governments to impose binding restraints on the federal government. We must use the power granted to the states in the Constitution.

Article 2 - The Lamp of Experience

The Lamp of Experience: Constitutional Amendments Work

Robert Natelson, Independence Institute’s Senior Fellow in Constitutional Jurisprudence and Head of the Institute’s Article V Information Center

Opponents of a Convention of States long argued there was an unacceptable risk that a convention might do too much. It now appears they were mistaken. So they increasingly argue that amendments cannot do enough.

The gist of this argument is that amendments would accomplish nothing because federal officials would violate amendments as readily as they violate the original Constitution.

Opponents will soon find their new position even less defensible than the old. This is be-cause the contention that amendments are useless flatly contradicts over two centuries of American experience — experience that demonstrates that amendments work. In fact, amendments have had a major impact on American political life, mostly for good.

The Framers inserted an amendment process into the Constitution to render the underlying system less fragile and more durable. They saw the amendment mechanism as a way to:

- correct drafting errors;

- resolve constitutional disputes, such as by reversing bad Supreme Court decisions;

- respond to changed conditions; and

- correct and forestall governmental abuse.

The Framers turned out to be correct, because in the intervening years we have adopted amendments for all four of those reasons. Today, nearly all of these amendments are accepted by the overwhelming majority of Americans, and all but very few remain in full effect. Possibly because ratification of a constitutional amendment is a powerful expression of popular political will, amendments have proved more durable than some parts of the original Constitution.

Following are some examples:

Correcting Drafting Errors

Although the Framers were very great people, they still were human, and they occasionally erred. Thus, they inserted into the Constitution qualifications for Senators,

Representatives, and the President, but omitted any for Vice President. They also adopted a presidential/vice presidential election procedure that, while initially plausible, proved unacceptable in practice.

The founding generation proposed and ratified the Twelfth Amendment to correct those mistakes. The Twenty-Fifth Amendment addressed some other deficiencies in Article II, which deals with the presidency. Both amendments are in full effect today.

Resolving Constitutional Disputes and Overruling the Supreme Court

The Framers wrote most of the Constitution in clear language, but they knew that, as with any legal document, there would be differences of interpretation. The amendment process was a way of resolving interpretive disputes.

The founding generation employed it for this purpose just seven years after the Constitution came into effect. In Chisholm v. Georgia, the Supreme Court misinterpreted the wording of Article III defining the jurisdiction of the federal courts. The Eleventh Amendment reversed that decision.

In 1857, the Court issued Dred Scott v. Sandford, in which it erroneously interpreted the Constitution to deny citizenship to African Americans. The Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment reversed that case.

In 1970, the Court decided Oregon v.Mitchell, whose misinterpretation of the Constitution created a national election law mess. A year later, Americans cleaned up the mess by ratifying the Twenty-Sixth Amendment.

All these amendments are in full effect today, and fully respected by the courts.

Responding to Changed Conditions

The Twentieth Amendment is the most obvious example of a response to changed conditions. Reflecting improvements in transportation since the Founding, it moved the inauguration of Congress and President from March to the January following election.

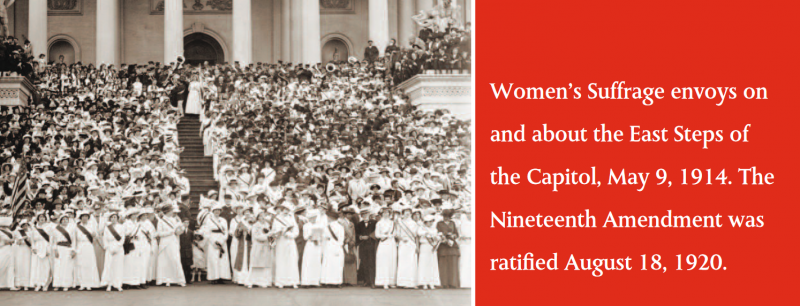

Similarly, the Nineteenth Amendment, which assured women the vote in states not already granting it, was passed for reasons beyond simple fairness. During the 1800s, medical and technological advances made possible by a vigorous market economy improved the position of women immeasurably and rendered their political participation far more feasible. Without these changes, I doubt the Nineteenth Amendment would have been adopted.

Needless to say, the Nineteenth and Twentieth Amendments are in full effect many years after they were ratified.

Correcting and Forestalling Government Abuse

Avoiding and correcting government abuse was a principal reason the Constitutional Convention unanimously inserted the state-driven convention procedure into Article V. Our failure to use that procedure helps explain why the earlier constitutional barriers against federal overreaching seem a little ragged. Before looking at the problems, how-ever, let’s look at some successes:

- We adopted the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, Fifteenth, and Twenty-Fourth Amendments to correct state abuses of power. All of these are in substantially full effect.

- In 1992, we ratified the Twenty-Seventh Amendment, 203 years after James Madison first proposed it. It limits congressional pay raises, although some would say not enough.

- In 1951, we adopted the Twenty-Second Amendment, limiting the President to two terms. Eleven Presidents later, it remains in full force, and few would contend it has not made a difference.

Now the problems: Because we have not used the convention process, the first 10 amendments (the Bill of Rights) remain almost the only amendments significantly limiting congressional overreaching. I suppose that if the Founders had listened to the “amendments won’t make any difference” crowd, they would not have adopted the Bill of Rights either. But I don’t know anyone to-day who seriously claims the Bill of Rights has made no difference.

“I have but one lamp by which my feet are guided; and that is the lamp of experience,” Patrick Henry said. “I know of no way of judging of the future but by the past.”

In this case, the lamp of experience sheds light unmistakably bright and clear: Constitutional amendments work.

Article 3 - Answering the Runaway Convention Myth

Can We Trust the Constitution? Answering The “Runaway Convention” Myth

By Michael Farris, JD, LLM

Some people contend that our Constitution was illegally adopted as the result of a “run-away convention.” They make two claims:

- The convention delegates were instructed to merely amend the Articles of Confederation, but they wrote a whole new document.

- The ratification process was improperly changed from 13 state legislatures to 9 state ratification conventions.

The Delegates Obeyed Their Instructions from the States

The claim that the delegates disobeyed their instructions is based on the idea that Congress called the Constitutional Convention. Proponents of this view assert that Congress limited the delegates to amending the Articles of Confederation. A review of legislative history clearly reveals the error of this claim. The Annapolis Convention, not Congress, provided the political impetus for calling the Constitutional Convention. The delegates from the 5 states participating at Annapolis concluded that a broader convention was needed to address the nation’s concerns. They named the time and date (Philadelphia; second Monday in May).

The Annapolis delegates said they were going to work to “procure the concurrence of the other States in the appointment of Commissioners.” The goal of the upcoming convention was “to render the constitution of the Federal Government adequate for the exigencies of the Union.”

What role was Congress to play in calling the Convention? None. The Annapolis delegates sent copies of their resolution to Congress solely “from motives of respect.”

What authority did the Articles of Confederation give to Congress to call such a Convention? None. The power of Congress under the Articles was strictly limited, and there was no theory of implied powers. The states possessed residual sovereignty which included the power to call this convention.

Seven state legislatures agreed to send delegates to the Constitutional Convention prior to the time that Congress acted to endorse it. The states told their delegates that the purpose of the Convention was the one stated in the Annapolis Convention resolution: “to render the constitution of the Federal Government adequate for the exigencies of the Union.”

Congress voted to endorse this Convention on February 21, 1787. It did not purport to “call” the Convention or give instructions to the delegates. It merely proclaimed that “in the opinion of Congress, it is expedient” for the Convention to be held in Philadelphia on the date informally set by the Annapolis Convention and formally approved by 7 state legislatures.

Ultimately, 12 states appointed delegates. Ten of these states followed the phrasing of the Annapolis Convention with only minor variations in wording (“render the Federal Constitution adequate”). Two states, New York and Massachusetts, followed the formula stated by Congress (“solely amend the Articles” as well as “render the Federal Constitution adequate”).

Every student of history should know that the instructions for delegates came from the states. In Federalist 40, James Madison answered the question of “who gave the binding instructions to the delegates.” He said: “The powers of the convention ought, in strictness, to be determined by an inspection of the commissions given to the members by their respective constituents [i.e. the states].” He then spends the balance of Federalist 40 proving that the delegates from all 12 states properly followed the directions they were given by each of their states. According to Madison, the February 21st resolution from Congress was merely “a recommendatory act.”

The States, not Congress, called the Constitutional Convention. They told their delegates to render the Federal Constitution adequate for the exigencies of the Union. And that is exactly what they did.

The Ratification Process Was Properly Changed

The Articles of Confederation required any amendments to be approved by Congress and ratified by all 13 state legislatures. Moreover, the Annapolis Convention and a clear majority of the states insisted that any amendments coming from the Constitutional Convention would have to be approved in this same manner—by Congress and all 13 state legislatures.

The reason for this rule can be found in the principles of international law. At the time, the states were sovereigns. The Articles of Confederation were, in essence, a treaty be-tween 13 sovereign nations. Normally, the only way changes in a treaty can be ratified is by the approval of all parties to the treaty.

However, a treaty can provide for some-thing less than unanimous approval if all the parties agree to a new approval process be-fore it goes into effect. This is exactly what the Founders did.

When the Convention sent its draft of the Constitution to Congress, it also recommended a new ratification process. Congress approved both the Constitution itself and the new process.

Along with changing the number of required states from 13 to 9, the new ratification process required that state conventions ratify the Constitution rather than state legislatures. This was done in accord with the preamble of the Constitution—the Supreme Law of the Land would be ratified in the name of “We the People” rather than “We the States.”

But before this change in ratification could be valid, all 13 state legislatures would also have to consent to the new method. All 13 state legislatures did just this by calling conventions of the people to vote on the merits of the Constitution.

Twelve states held popular elections to vote for delegates. Rhode Island made every voter a delegate and held a series of town meetings to vote on the Constitution. Thus, every state legislature consented to the new ratification process thereby validating the Constitution’s requirements for ratification.

Those who claim to be constitutionalists while contending that the Constitution was illegally adopted are undermining themselves. It is like saying George Washington was a great American hero, but he was also a British spy. I stand with the integrity of our Founders who properly drafted and properly ratified the Constitution.

Article 4 - Is the Second Amendment at Risk

An Open Letter Concerning The Second Amendment and The Convention of States Project

Our constitutional rights, especially our Second Amendment right to keep and bear arms, are in peril. With every tragic violent crime, liberals renew their demands for Congress and state legislatures to enact so-called “commonsense gun control” measures designed to chip away at our individual constitutional right to armed self defense. Indeed, were it not for the determination and sheer political muscle of the National Rifle Association, Senator Feinstein’s 2013 bill to outlaw so-called “assault weapons” and other firearms might well have passed. But the most potent threat facing the Second Amendment comes not from Congress, but from the Supreme Court. Four justices of the Supreme Court do not believe that the Second Amendment guarantees an individual right to keep and bear arms. They believe that Congress and state legislatures are free not only to restrict firearms owner-ship by law-abiding Americans, but to ban firearms altogether. If the Liberals get one more vote on the Supreme Court, the Second Amendment will be no more.

Constitutional law has been the dominant focus of my practice for most of my career as a lawyer, first in the Justice Department as President Reagan’s chief constitutional lawyer and the chairman of the President’s Working Group on Federalism, and since then as a constitutional litigator in private practice. For almost three decades, I have represented dozens of states and many other clients in constitutional cases, including many Second Amendment cases. In 2001, for example, I argued the first federal appellate case to hold that the Second Amendment guarantees every law-abiding responsible adult citizen an individual right to keep and bear arms. And in 2013 I testified before the Senate in opposition to Senator Feinstein’s anti-gun bill, arguing that it would violate the Second Amendment. So I am not accustomed to being accused of supporting a scheme that would “put our Second Amendment rights on the chopping block.” This charge is being hurled by a small gun-rights group against me and many other constitutional conservatives because we have urged the states to use their sovereign power under Article V of the Constitution to call for a convention for proposing constitutional amendments designed to rein in the federal government’s power.

The real threat to our constitutional rights today is posed not by an Article V convention of the states, but by an out-of-control federal government, exercising powers that it does not have and abusing powers that it does.

The federal government’s unrelenting encroachment upon the sovereign rights of the states and the individual rights of citizens, and the Supreme Court’s failure to prevent it, have led me to join the Legal Board of Reference for the Convention of States Project. The Project’s mission is to urge 34 state legislatures to call for an Article V convention limited to proposing constitutional amendments that “impose fiscal restraints on the federal government, limit its power and jurisdiction, and impose term limits on its officials and members of Congress.” I am joined in this effort by many well-known constitutional conservatives, including Mark Levin, Professor Randy Barnett, Professor Robert George, Michael Farris, Mark Meckler, Professor Robert Natelson, Andrew McCarthy, Professor John Eastman, Ambassador Boyden Gray, and Professor Nelson Lund. All of us have carefully studied the original meaning of Article V, and not one of us would support an Article V convention if we believed it would pose a significant threat to our Second Amendment rights or any of our constitutional freedoms. To the contrary, our mission is to reclaim our democratic and individual freedoms from an overreaching federal government.

—-

The Framers of our Constitution carefully limited the federal government’s powers by specifically enumerating those powers in Article I, and the states promptly ensured that the Constitution would expressly protect the “right of the people to keep and bear arms” by adopting the Second Amendment. But the Framers understood human nature, and they could foresee a day when the federal government would yield to the “encroaching spirit of power,” as James Madison put in the Federalist Papers, and would invade the sovereign domain of the states and infringe the rights of the citizens. The Framers also knew that the states would be powerless to remedy the federal government’s encroachments if the process of amending the Constitution could be initiated only by Congress; as Alexander Hamilton noted in the Federalist Papers, “the national government will always be disinclined to yield up any portion of the authority” it claims. So the Framers wisely equipped the states with the means of reclaiming their sovereign powers and protecting the rights of their citizens, even in the face of congressional opposition. Article V vests the states with unilateral power to convene for the purpose of proposing constitutional amendments and to control the amending process from beginning to end on all substantive matters.

—-

The Framers of our Constitution carefully limited the federal government’s powers by specifically enumerating those powers in Article I, and the states promptly ensured that the Constitution would expressly protect the “right of the people to keep and bear arms” by adopting the Second Amendment. But the Framers understood human nature, and they could foresee a day when the federal government would yield to the “encroaching spirit of power,” as James Madison put in the Federalist Papers, and would invade the sovereign domain of the states and infringe the rights of the citizens. The Framers also knew that the states would be powerless to remedy the federal government’s encroachments if the process of amending the Constitution could be initiated only by Congress; as Alexander Hamilton noted in the Federalist Papers, “the national government will always be disinclined to yield up any portion of the authority” it claims. So the Framers wisely equipped the states with the means of reclaiming their sovereign powers and protecting the rights of their citizens, even in the face of congressional opposition. Article V vests the states with unilateral power to convene for the purpose of proposing constitutional amendments and to control the amending process from beginning to end on all substantive matters.

The day foreseen by the Framers – the day when the federal government far exceeded the limits of its enumerated powers – arrived many years ago. The Framers took care in Article V to equip the people, acting through their state legislatures, with the power to put a stop to it. It is high time they used it.

Charles J. Cooper is a founding member and chairman of Cooper & Kirk, PLLC. Named by The National Law Journal as one of the 10 best civil litigators in Washington, he has over 35 years of legal experience in government and private practice, with several appearances before the United States Supreme Court and scores of other successful cases on both the trial and appellate levels.

COS Surge Article Library

Article 1 - Solution As Big As Problem

Article 2 - The lamp of experience: Constitutional Amendments Work

Article 3 - Answering the Runaway Convention Myth

Article 4 - Is the Second Amendment at Risk?

Article 6 - How the Courts have clarified the Constitution’s Amendment Process

Article 7 - Myth Runaway Amend Convention

Article 8 - Already Adopted a Balance Budget Amendment

Article 9 - Let’s provide our children with common sense, not common core

Article 10 - Final Constitutional Option

Article 12 - Article V Solution

Article 13 - Five Myths About An Article V Convention

Article 14 - An Article V Convention is not a Constitutional Convention

Article 15 - Time to Evict Squatters

Article 16 - Implement Tenth Amendment

Article 17 - Address State Budget Challenges

Article 18 - Demystifying a Dusty Tool

Article 19 - Corrupting Influence Money In Politics

Article 20 - Necessary Proper Clause

Article 21 - John Birch Society

Article 22 - Article V Process

Article 23 - Federal Control Lands

COS Surge Article Library

Article 1 - Solution As Big As Problem

Article 2 - The lamp of experience: Constitutional Amendments Work

Article 3 - Answering the Runaway Convention Myth

Article 4 - Is the Second Amendment at Risk?

Article 6 - How the Courts have clarified the Constitution’s Amendment Process

Article 7 - Myth Runaway Amend Convention

Article 8 - Already Adopted a Balance Budget Amendment

Article 9 - Let’s provide our children with common sense, not common core

Article 10 - Final Constitutional Option

Article 12 - Article V Solution

Article 13 - Five Myths About An Article V Convention

Article 14 - An Article V Convention is not a Constitutional Convention

Article 15 - Time to Evict Squatters

Article 16 - Implement Tenth Amendment

Article 17 - Address State Budget Challenges

Article 18 - Demystifying a Dusty Tool

Article 19 - Corrupting Influence Money In Politics

Article 20 - Necessary Proper Clause

Article 21 - John Birch Society

Article 22 - Article V Process

Article 23 - Federal Control Lands

COS Surge Article Library

Article 1 - Solution As Big As Problem

Article 2 - The lamp of experience: Constitutional Amendments Work

Article 3 - Answering the Runaway Convention Myth

Article 4 - Is the Second Amendment at Risk?

Article 6 - How the Courts have clarified the Constitution’s Amendment Process

Article 7 - Myth Runaway Amend Convention

Article 8 - Already Adopted a Balance Budget Amendment

Article 9 - Let’s provide our children with common sense, not common core

Article 10 - Final Constitutional Option

Article 12 - Article V Solution

Article 13 - Five Myths About An Article V Convention

Article 14 - An Article V Convention is not a Constitutional Convention

Article 15 - Time to Evict Squatters

Article 16 - Implement Tenth Amendment

Article 17 - Address State Budget Challenges

Article 18 - Demystifying a Dusty Tool

Article 19 - Corrupting Influence Money In Politics

Article 20 - Necessary Proper Clause

Article 21 - John Birch Society

Article 22 - Article V Process

Article 23 - Federal Control Lands

COS Surge Article Library

Article 1 - Solution As Big As Problem

Article 2 - The lamp of experience: Constitutional Amendments Work

Article 3 - Answering the Runaway Convention Myth

Article 4 - Is the Second Amendment at Risk?

Article 6 - How the Courts have clarified the Constitution’s Amendment Process

Article 7 - Myth Runaway Amend Convention

Article 8 - Already Adopted a Balance Budget Amendment

Article 9 - Let’s provide our children with common sense, not common core

Article 10 - Final Constitutional Option

Article 12 - Article V Solution

Article 13 - Five Myths About An Article V Convention

Article 14 - An Article V Convention is not a Constitutional Convention

Article 15 - Time to Evict Squatters

Article 16 - Implement Tenth Amendment

Article 17 - Address State Budget Challenges

Article 18 - Demystifying a Dusty Tool

Article 19 - Corrupting Influence Money In Politics

Article 20 - Necessary Proper Clause

Article 21 - John Birch Society

Article 22 - Article V Process

Article 23 - Federal Control Lands

COS Surge Article Library

Article 1 - Solution As Big As Problem

Article 2 - The lamp of experience: Constitutional Amendments Work

Article 3 - Answering the Runaway Convention Myth

Article 4 - Is the Second Amendment at Risk?

Article 6 - How the Courts have clarified the Constitution’s Amendment Process

Article 7 - Myth Runaway Amend Convention

Article 8 - Already Adopted a Balance Budget Amendment

Article 9 - Let’s provide our children with common sense, not common core

Article 10 - Final Constitutional Option

Article 12 - Article V Solution

Article 13 - Five Myths About An Article V Convention

Article 14 - An Article V Convention is not a Constitutional Convention

Article 15 - Time to Evict Squatters

Article 16 - Implement Tenth Amendment

Article 17 - Address State Budget Challenges

Article 18 - Demystifying a Dusty Tool

Article 19 - Corrupting Influence Money In Politics

Article 20 - Necessary Proper Clause

Article 21 - John Birch Society

Article 22 - Article V Process

Article 23 - Federal Control Lands

COS Surge Article Library

Article 1 - Solution As Big As Problem

Article 2 - The lamp of experience: Constitutional Amendments Work

Article 3 - Answering the Runaway Convention Myth

Article 4 - Is the Second Amendment at Risk?

Article 6 - How the Courts have clarified the Constitution’s Amendment Process

Article 7 - Myth Runaway Amend Convention

Article 8 - Already Adopted a Balance Budget Amendment

Article 9 - Let’s provide our children with common sense, not common core

Article 10 - Final Constitutional Option

Article 12 - Article V Solution

Article 13 - Five Myths About An Article V Convention

Article 14 - An Article V Convention is not a Constitutional Convention

Article 15 - Time to Evict Squatters

Article 16 - Implement Tenth Amendment

Article 17 - Address State Budget Challenges

Article 18 - Demystifying a Dusty Tool

Article 19 - Corrupting Influence Money In Politics

Article 20 - Necessary Proper Clause

Article 21 - John Birch Society

Article 22 - Article V Process

Article 23 - Federal Control Lands

COS Surge Article Library

Article 1 - Solution As Big As Problem

Article 2 - The lamp of experience: Constitutional Amendments Work

Article 3 - Answering the Runaway Convention Myth

Article 4 - Is the Second Amendment at Risk?

Article 6 - How the Courts have clarified the Constitution’s Amendment Process

Article 7 - Myth Runaway Amend Convention

Article 8 - Already Adopted a Balance Budget Amendment

Article 9 - Let’s provide our children with common sense, not common core

Article 10 - Final Constitutional Option

Article 12 - Article V Solution

Article 13 - Five Myths About An Article V Convention

Article 14 - An Article V Convention is not a Constitutional Convention

Article 15 - Time to Evict Squatters

Article 16 - Implement Tenth Amendment

Article 17 - Address State Budget Challenges

Article 18 - Demystifying a Dusty Tool

Article 19 - Corrupting Influence Money In Politics

Article 20 - Necessary Proper Clause

Article 21 - John Birch Society

Article 22 - Article V Process

Article 23 - Federal Control Lands

COS Surge Article Library

Article 1 - Solution As Big As Problem

Article 2 - The lamp of experience: Constitutional Amendments Work

Article 3 - Answering the Runaway Convention Myth

Article 4 - Is the Second Amendment at Risk?

Article 6 - How the Courts have clarified the Constitution’s Amendment Process

Article 7 - Myth Runaway Amend Convention

Article 8 - Already Adopted a Balance Budget Amendment

Article 9 - Let’s provide our children with common sense, not common core

Article 10 - Final Constitutional Option

Article 12 - Article V Solution

Article 13 - Five Myths About An Article V Convention

Article 14 - An Article V Convention is not a Constitutional Convention

Article 15 - Time to Evict Squatters

Article 16 - Implement Tenth Amendment

Article 17 - Address State Budget Challenges

Article 18 - Demystifying a Dusty Tool

Article 19 - Corrupting Influence Money In Politics

Article 20 - Necessary Proper Clause

Article 21 - John Birch Society

Article 22 - Article V Process

Article 23 - Federal Control Lands

COS Surge Article Library

Article 1 - Solution As Big As Problem

Article 2 - The lamp of experience: Constitutional Amendments Work

Article 3 - Answering the Runaway Convention Myth

Article 4 - Is the Second Amendment at Risk?

Article 6 - How the Courts have clarified the Constitution’s Amendment Process

Article 7 - Myth Runaway Amend Convention

Article 8 - Already Adopted a Balance Budget Amendment

Article 9 - Let’s provide our children with common sense, not common core

Article 10 - Final Constitutional Option

Article 12 - Article V Solution

Article 13 - Five Myths About An Article V Convention

Article 14 - An Article V Convention is not a Constitutional Convention

Article 15 - Time to Evict Squatters

Article 16 - Implement Tenth Amendment

Article 17 - Address State Budget Challenges

Article 18 - Demystifying a Dusty Tool

Article 19 - Corrupting Influence Money In Politics

Article 20 - Necessary Proper Clause

Article 21 - John Birch Society

Article 22 - Article V Process

Article 23 - Federal Control Lands

COS Surge Article Library

Article 1 - Solution As Big As Problem

Article 2 - The lamp of experience: Constitutional Amendments Work

Article 3 - Answering the Runaway Convention Myth

Article 4 - Is the Second Amendment at Risk?

Article 6 - How the Courts have clarified the Constitution’s Amendment Process

Article 7 - Myth Runaway Amend Convention

Article 8 - Already Adopted a Balance Budget Amendment

Article 9 - Let’s provide our children with common sense, not common core

Article 10 - Final Constitutional Option

Article 12 - Article V Solution

Article 13 - Five Myths About An Article V Convention

Article 14 - An Article V Convention is not a Constitutional Convention

Article 15 - Time to Evict Squatters

Article 16 - Implement Tenth Amendment

Article 17 - Address State Budget Challenges

Article 18 - Demystifying a Dusty Tool

Article 19 - Corrupting Influence Money In Politics

Article 20 - Necessary Proper Clause

Article 21 - John Birch Society

Article 22 - Article V Process

Article 23 - Federal Control Lands

COS Surge Article Library

Article 1 - Solution As Big As Problem

Article 2 - The lamp of experience: Constitutional Amendments Work

Article 3 - Answering the Runaway Convention Myth

Article 4 - Is the Second Amendment at Risk?

Article 6 - How the Courts have clarified the Constitution’s Amendment Process

Article 7 - Myth Runaway Amend Convention

Article 8 - Already Adopted a Balance Budget Amendment

Article 9 - Let’s provide our children with common sense, not common core

Article 10 - Final Constitutional Option

Article 12 - Article V Solution

Article 13 - Five Myths About An Article V Convention

Article 14 - An Article V Convention is not a Constitutional Convention

Article 15 - Time to Evict Squatters

Article 16 - Implement Tenth Amendment

Article 17 - Address State Budget Challenges

Article 18 - Demystifying a Dusty Tool

Article 19 - Corrupting Influence Money In Politics

Article 20 - Necessary Proper Clause

Article 21 - John Birch Society

Article 22 - Article V Process

Article 23 - Federal Control Lands

COS Surge Article Library

Article 1 - Solution As Big As Problem

Article 2 - The lamp of experience: Constitutional Amendments Work

Article 3 - Answering the Runaway Convention Myth

Article 4 - Is the Second Amendment at Risk?

Article 6 - How the Courts have clarified the Constitution’s Amendment Process

Article 7 - Myth Runaway Amend Convention

Article 8 - Already Adopted a Balance Budget Amendment

Article 9 - Let’s provide our children with common sense, not common core

Article 10 - Final Constitutional Option

Article 12 - Article V Solution

Article 13 - Five Myths About An Article V Convention

Article 14 - An Article V Convention is not a Constitutional Convention

Article 15 - Time to Evict Squatters

Article 16 - Implement Tenth Amendment

Article 17 - Address State Budget Challenges

Article 18 - Demystifying a Dusty Tool

Article 19 - Corrupting Influence Money In Politics

Article 20 - Necessary Proper Clause

Article 21 - John Birch Society

Article 22 - Article V Process

Article 23 - Federal Control Lands

COS Surge Article Library

Article 1 - Solution As Big As Problem

Article 2 - The lamp of experience: Constitutional Amendments Work

Article 3 - Answering the Runaway Convention Myth

Article 4 - Is the Second Amendment at Risk?

Article 6 - How the Courts have clarified the Constitution’s Amendment Process

Article 7 - Myth Runaway Amend Convention

Article 8 - Already Adopted a Balance Budget Amendment

Article 9 - Let’s provide our children with common sense, not common core

Article 10 - Final Constitutional Option

Article 12 - Article V Solution

Article 13 - Five Myths About An Article V Convention

Article 14 - An Article V Convention is not a Constitutional Convention

Article 15 - Time to Evict Squatters

Article 16 - Implement Tenth Amendment

Article 17 - Address State Budget Challenges

Article 18 - Demystifying a Dusty Tool

Article 19 - Corrupting Influence Money In Politics

Article 20 - Necessary Proper Clause

Article 21 - John Birch Society

Article 22 - Article V Process

Article 23 - Federal Control Lands

COS Surge Article Library

Article 1 - Solution As Big As Problem

Article 2 - The lamp of experience: Constitutional Amendments Work

Article 3 - Answering the Runaway Convention Myth

Article 4 - Is the Second Amendment at Risk?

Article 6 - How the Courts have clarified the Constitution’s Amendment Process

Article 7 - Myth Runaway Amend Convention

Article 8 - Already Adopted a Balance Budget Amendment

Article 9 - Let’s provide our children with common sense, not common core

Article 10 - Final Constitutional Option

Article 12 - Article V Solution

Article 13 - Five Myths About An Article V Convention

Article 14 - An Article V Convention is not a Constitutional Convention

Article 15 - Time to Evict Squatters

Article 16 - Implement Tenth Amendment

Article 17 - Address State Budget Challenges

Article 18 - Demystifying a Dusty Tool

Article 19 - Corrupting Influence Money In Politics

Article 20 - Necessary Proper Clause

Article 21 - John Birch Society

Article 22 - Article V Process

Article 23 - Federal Control Lands