Table of Contents

John Birch Society Denies Its History and Betrays Its Mission

Posted by Ken Quinn on April 15, 2015 (source)

In a recent article entitled “Falsehoods Mark the Campaign for a Constitutional Convention,” the John Birch Society (JBS) President John McManus, paints a picture of longstanding, consistent JBS opposition to the use of Article V's convention mechanism. He states:

“For one excellent reason, The John Birch Society has always opposed the creation of a constitutional convention (Con-Con) as authorized in Article V of the Constitution.” 1)

“Some [Article V] proponents also claim that John Birch Society Founder Robert Welch and Congressman Larry McDonald, his 1983 successor, advocated the Con-Con route in favor of the “The Liberty Amendment.””

“But neither Robert Welch nor Larry McDonald nor this writer (current JBS President) has ever advocated a Con-Con on behalf of the Liberty Amendment or any other amendment.”

But McManus' claim that JBS has always opposed a convention under Article V is simply not accurate.

Let's go back in time and see how all of this unfolds. In 1944, Willis E. Stone drafted the Liberty Amendment, which sought to vastly restrict federal authority and repeal the Sixteenth Amendment. Nine states passed Liberty Amendment resolutions.

Here is the text from Louisiana's resolution:

“Be it Resolved by the House of Representatives of the State of Louisiana, the Senate concurring, that we respectfully request the Congress of the United States to propose to the people an amendment to the Constitution of the United States, or to call a convention for such purpose as provided by Article V of the Constitution, an article providing as follows:

ARTICLE_______

Sec. 1: The Government of the United States shall not engage in any business, professional, commercial, financial or industrial enterprise except as specified in the Constitution.

Sec. 2: The Constitution or laws of any State, or the laws of the United States, shall not be subject to the terms of any foreign or domestic agreement which would abrogate this amendment.

Sec. 3: The activities of the United States Government which violate the intent and purposes of this amendment shall, within a period of three years from the date of the ratification of this amendment, be liquidated and the properties and facilities affected shall be sold.

Sec. 4: Three years after the ratification of this amendment the sixteenth article of amendments to the Constitution of the United States shall stand repealed and thereafter Congress shall not levy taxes on personal incomes, estates, and/or gifts.

(emphasis added).

One would have expected The John Birch Society and its leaders–who profess to advocate for limited government–to have been strong advocates of these resolutions. And that is exactly what they were under the leadership of Robert Welch and Larry McDonald back in the 1960s-1980s.

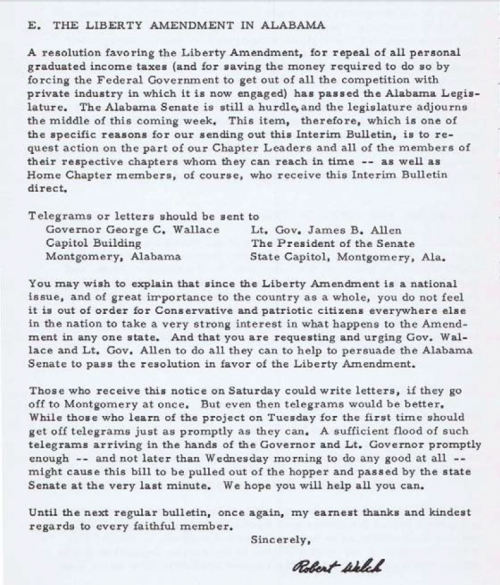

Here is The John Birch Society Bulletin for August, 1963, with an urgent message from Robert Welch asking all Chapter Leaders and members to send telegrams and letters urging the Alabama Senate to pass the resolution calling for the Liberty Amendment.

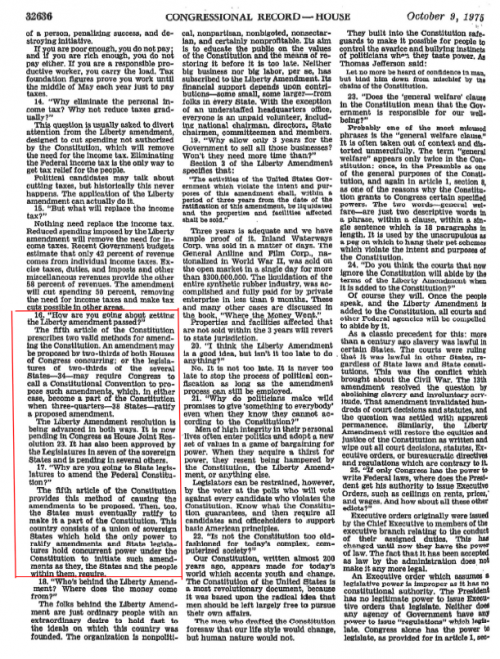

RepresentativeLarry McDonald, from Georgia, who served at the time on the John Birch Society's National Council, introduced the Liberty Amendment in Congress on October 9, 1975 and gave extensive testimony–including responses to 74 questions about the amendment. Among those questions and answers were the following:

(Congressional Record – House, October 9, 1975, 32634-32641)

16. “How are you going about getting the Liberty Amendment passed?”

“The fifth article of the Constitution prescribes two valid methods for amending the Constitution. An amendment may be proposed by two-thirds of both Houses of Congress concurring; or the legislatures of two-thirds of the several States—34—may require Congress to call a Constitutional Convention to propose such amendments, which, in either case, become a part of the Constitution when three-quarters—38 States—ratify a proposed amendment.

The Liberty Amendment resolution is being advanced in both ways. It is now pending in Congress as House Joint Resolution 23. It has also been approved by the Legislatures in seven of the sovereign States and is pending in several others.”

17. “Why are you going to State legislatures to amend the Federal Constitution?”

“The fifth article of the Constitution provides this method of causing the amendments to be proposed. Then, too, the States must eventually ratify to make it a part of the Constitution. This country consists of a union of sovereign States which hold the only power to ratify amendments and State legislatures hold concurrent power under the Constitution to initiate such amendments as they, the States and the people within them, require.” Congressional Record - House, October 9, 1975, 32634-32641.

The record speaks for itself. And it flies in the face of McManus' insistence that ”[N]either Robert Welch nor Larry McDonald . . . has ever advocated a Con-Con on behalf of the Liberty Amendment or any other amendment.“

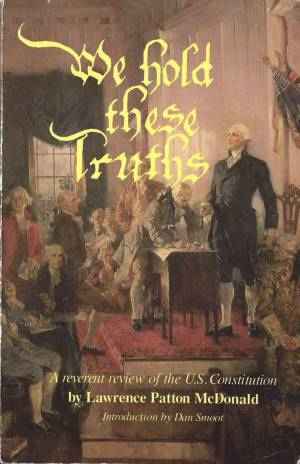

It would behoove Mr. McManus to read Larry McDonald's book, We Hold These Truths, published a year after his testimony, for in it McDonald explains the reasons why he advocates strongly for an Article V convention:

“The Framers provided means for the people to amend the Constitution-means which virtually circumvent federal officials. The President and the federal courts are given no role whatever in the amendment process. Congress is authorized to propose constitutional amendments if it pleases. It is obligated to call a special convention to propose constitutional amendments if two-thirds of all state legislatures demand that it do so; but Congress is given no hand in the actual ratifying or rejecting of proposed amendments. The amendment process is slow, and it was made so deliberately, in making changes in their organic law, people should not be stampeded by demagoguery, mob psychology, or false promises. The public should have ample time to think, study, debate, and reflect before making constitutional changes that affect all of them and their posterity. As James Madison put it, the amendment process was designed specifically to “guard…against that extreme facility, which would render the Constitution too mutable.” Lawrence Patton McDonald We Hold These Truths (The Larry McDonald Memorial Foundation Inc. Marietta Georgia, 1976), 27.

On January 3, 1983, Rep. Larry McDonald introduced the Liberty Amendment again in Congress, co-sponsoring H.R. 23 along with Rep. Ron Paul. Two months later on March 14th, Larry McDonald succeeded Robert Welch as Chairman of The John Birch Society. Sadly, on September 1, 1983, McDonald was killed when Korean Air Lines flight 007 was shot down by a Soviet MIG fighter jet.

So how does Mr. McManus deny all of this evidence? Here is his answer:

”I vividly recall questioning Willis Stone about the danger that 34 states would indeed call for a Con-Con. I noted that if that number of state applications for a convention were reached, then the Constitution requires that Congress “shall call a convention for proposing amendments.” He emphatically assured me, “No, I don't worry about that because no one is stupid enough to want a Con-Con.”

But listen to Willis E. Stone, in his own words, describing states' actions upon his proposed amendment. Here are some of the state resolutions mentioned by Mr. Stone, all calling for an Article V convention to propose the Liberty Amendment:

Wyoming Article V Resolution for the Liberty Amendment, 1959

Nevada Article V Resolution for the Liberty Amendment 1960

Louisiana Article V Resolution for the Liberty Amendment 1960

South Carolina Article V Resolution for the Liberty Amendment 1962

McManus can say what he likes about Mr. Stone's internal feelings about the Article V convention process; but the best evidence of Mr. Stone's position is surely Mr. Stone's actions—which were clearly dedicated to promoting an Article V convention.

Despite McManus' claims to the contrary, the undisputed evidence also demonstrates that former JBS leaders themselves, Welch and McDonald, advocated for an Article V convention to propose the Liberty Amendment. This was consistent with the JBS' mission of limiting government.

It is the current JBS position, in opposition to the use of Article V's convention mechanism to limit the federal government, which is both inconsistent with that mission, and a departure from the organization's own, original position on Article V.

In fact, under its current leadership, the JBS has gone so far as to reverse itself not only on the general idea of Article V, but even on its support for the Liberty Amendment, in particular. It is now working to rescind the Liberty Amendment resolutions that Welch and McDonald helped the states to propose. Here isArizona's Article V Resolution for the Liberty Amendment in 1979and here isArizona's Rescind Resolution of 2003. Notice that the rescind language comes straight out of The John Birch Society Model Resolution for a State Legislature to Rescind All Constitutional Convention Applications. In his recent article, Mr. McManus states, ”Anyone who claims that JBS leaders (past or present) ever intended to have Congress create a constitutional convention either doesn't know what he or she is talking about or is being deceitful.“

At this point it is left to you, the reader, to decide who is being deceitful.

The Article Five solution – courage is the price of liberty

Posted by Rita Dunaway on March 13, 2015 (source)

This is the last installment in a five-part series on Article Five of the U.S. Constitution published on TheBlaze.com. Please check back every day this week for new content and click here for the entire series.

Throughout this series, I have argued that an Article Five amendment-proposing convention offers a viable and well-designed process for the states to rein in a runaway federal government and restore our Republic. In fact, I believe this process may well be the only way to close the court-created loopholes to our Constitution's original limitations on federal power.

The process is as safe as any political process can be, entailing numerous, redundant protections.

First, the scope of authority for the convention is set by the topic specified in the 34 applications that trigger the convention. So if 34 states apply for a convention to propose amendments that limit federal power, any proposals beyond that scope would be out of order.

Second, state legislatures can recall any delegates who exceed their authority or instructions. As a matter of basic agency law, actions taken outside the scope of a delegate's authority would be void.

Third, even if a majority of convention delegates went rogue and were left unchecked by the state legislatures they represent, and even if Congress nevertheless sent the illicit amendment proposals to the states for ratification, the courts could intervene to declare the proposals void. While the courts don't have a wonderful track record in interpreting broad constitutional language, they do have an excellent track record of enforcing clear, technical matters of procedure and agency law.

But the most important protection on the Article Five process is the explicit constitutional requirement that three-fourths, or 38, of the states must ratify any proposed amendments in order for them to become effective. This means that any bad amendment can be blocked by only 13 states.

In light of the multiple layers of protection on the state-led Article Five convention process, it is difficult to understand why some are so afraid of it-or why they don't seem to fear Congress' parallel Article Five power to propose amendments on any subject, any day it sits in session.

Certainly, no future outcome of any kind can ever be absolutely guaranteed. Day has dawned since the beginning of time, but who can definitively prove that the sun will rise tomorrow?

What critics must acknowledge, however, is that the proper risk analysis is a comparative one. It would be difficult for anyone to maintain, with a straight face, that the risk of a state-led amendment-proposing convention is greater than the risk of staying our current course.

The “risk” (which, again, exists only in the sense that nothing is entirely risk-free) is negligible. But to those who can't see around it, I posit this: Courage is the price of liberty. It always has been, and it always will be.

Courage was the ink that marked the words of the Declaration of Independence onto the opening chapter of America. It was the boat that carried Gen. George Washington across the Delaware River.

Courage was the tattered uniform of young men who gave their lives to rid a fledgling America of the scourge of slavery. It was the tank that carried weary soldiers over the battlefields of a Hitler-stained Europe. And courage was the voice of Martin Luther King, Jr., challenging America to end her hypocrisy and make good on her commitment to the legal equality of mankind.

America exists because our forefathers pledged their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor to secure for us the blessings of liberty and the right of self-governance. They left us Article Five's convention process to ensure that we would have a final defense against federal tyranny. If our generation is so frozen in fear that we lack the modicum of courage required to hold a meeting, then we are simply unworthy of our heritage.

Courage is the price of liberty.

Rita Martin Dunaway serves as Staff Counsel for The Convention of States Project and is passionate about restoring constitutional governance in the U.S. Follow her on Facebook (Rita Martin Dunaway) and e-mail her at rita.dunaway@gmail.com.

The Article Five solution – The Founders would want us to use it

Posted by Rita Dunaway on March 12, 2015 (source)

This is the fourth installment in a five-part series on Article Five of the U.S. Consitution. Please check back every day this week for new content and click here for the entire series.

As I have explained in previous articles in this series, most conservative opponents to Article Five's convention process are people who revere our Founding Fathers and the Constitution they created.

While the brave and brilliant men who devised our ingenious federal system are certainly deserving of our profound respect, admiration, and gratitude, the idea that they were perfect, infallible statesmen—and that the Constitution is untouchable Holy Writ—is antithetical to their own worldview. And it is that worldview which inspired our government's unique design.

Federalist 51 says it best:

It may be a reflection on human nature, that such devices should be necessary to control the abuses of government. But what is government itself, but the greatest of all reflections on human nature? If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.

Thus, the Constitution establishes a government replete with checks and balances designed to make “ambition to counteract ambition.”

At least, that was the plan. As I explained here, the three branches of our federal government are now acting in concert to further concentrate federal power at the expense of state power and individual liberty.

The Founders predicted this and planned for it. As I explained here, they provided the states with a means of imposing additional checks on all three branches of the federal government. They designed Article Five's convention process specifically to correct any improper aggregation of power.

Good government is simply not a once-and-for-all proposition. At a minimum, it requires our continual exertion to elect “good” public officials. But because we don't do that perfectly, and because even “good” public officials aren't perfect, good government requires various adjustments, at various times, to realign its operating structure with the blueprint.

The bold declaration that “all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights” was entirely inconsistent with the ongoing practice of slavery at our founding. It was perfect in principle, yet demanded the blood, sweat and tears of future generations—and a constitutional amendment—to effectuate.

Most modern inconsistencies between constitutional principle and practice result from interpretations of the language that conflict with its original meaning. Because the natural ambition of man has led congresses, presidents, and courts to seize power at every point of textual vagueness or ambiguity, modern Americans now confront the task of solidifying the original structure and fortifying limitations on federal power.

We must use the tools at our disposal to conform our government's operating structure to the blueprint.

I once assembled a desk using pre-fabricated components, a few tools, and an instruction booklet. When the project was finished, I discovered that I had inadvertently fastened the drawer to the desktop in such a way that the drawer cannot be opened.

Now I can shout, “Open!” at the drawer, or I can complain about my faulty interpretation of the instructions, but the only way I will ever achieve a functioning drawer is to remove the improperly constructed pieces and replace them, paying careful attention to the instructions.

Our Constitution is the operating manual for our government. At times, those charged with interpreting the manual have erred, and erred badly. The result is a dysfunctional federal system.

Those who have read the instructions and understood them can shout “Obey the Constitution!” to federal officials. We can be angry at those who have either purposefully or incompetently interpreted the manual to produce the mutated system we have today. But none of this will set things right.

The only way we will ever return to a properly functioning federal system is by repairing the damage that has been done to it through specific, unambiguous constitutional amendments that reject and replace the offending workmanship.

It isn't disloyal to the Founders to propose constitutional amendments. In fact, the surest way to honor their legacy is to emulate them. They knew themselves to be imperfect, and yet they summoned their courage and acted in pursuit of the high ideal of self-governance. We must do likewise.

Rita Martin Dunaway serves as Staff Counsel for The Convention of States Project and is passionate about restoring constitutional governance in the U.S. Follow her on Facebook (Rita Martin Dunaway) and e-mail her at rita.dunaway@gmail.com.

The Article Five solution – the way to implement the 10th Amendment

Posted by Rita Dunaway on March 11, 2015 (source)

This is the third installment in a five-part series on Article Five of the U.S. Constitution published on TheBlaze.com. Please check back every day this week for new content and click here for the entire series.

It's the elephant in the room. The 10th Amendment boldly declares:

The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the states respectively, or to the people.

But if the daily news is any indication, there is no subject exempt from federal power. Through its power of the purse, which is virtually unlimited under the modern interpretation, Congress can impact, influence, or coerce behavior in nearly every aspect of life.

The question, then, that holds the key to unlocking our constitutional quandary, is this: how do states protect their reserved powers under the 10th Amendment?

On a piecemeal basis, states can certainly challenge federal actions through lawsuits, arguing that the federal government lacks constitutional authority to act in a particular area. But what if the court, as it is wont to do, “interprets” the Constitution as providing the disputed authority? What then?

In their frustration and disbelief over the growing extent of federal abuses of power (and the refusal of our Supreme Court to correct them), some conservatives argue that states should engage in “nullification,” whereby the states simply refuse to comply with federal laws they deem unconstitutional.

While there are some, less dramatic forms of nullification that are perfectly appropriate and constitutional—such as states refusing to accept federal funds that come attached to federal requirements—this state-by-state, ad hoc review of federal law is fraught with legal and practical pitfalls.

First of all, which state officer, institution, or individual decides whether a federal action is authorized under the Constitution? Is it the state supreme court, the legislature, the attorney general—or can any individual make the determination? After all, the 10th Amendment reserves powers to individuals as well as to states.

Secondly, how can a state enforce its nullification of a federal law? For instance, if a state decides that the Affordable Care Act's individual mandate is unconstitutional, how can it protect its citizens against the “tax” that will be levied against them if they fail to comply? It's difficult to envision an effective nullification enforcement method that doesn't end, at some point, with armed conflict.

But for true conservatives whose goal is to conserve the original design of our federal system, the far more fundamental problem with this type of in-your-face nullification is the fact that it was not the Founders' plan.

Article Six tells us that the Constitution, and federal laws passed pursuant to it, are the “supreme law of the land.” Under Article Three, the United States Supreme Court is considered to be the final interpreter of the Constitution. While some claim that this was not the Founders' intention, historical records such as Alexander Hamilton's Federalist 78 demonstrate it was, in fact, the judiciary that they intended to assess the constitutionality of legislative acts.

And then we have the 10th Amendment itself. It establishes a principle, but it does not establish a remedyor process for protecting the reserved powers from federal intrusion.

That missing process is found in Article Five. Faced with a federal government acting beyond the scope of its legitimate powers—and a Supreme Court that adopts erroneous interpretations of the Constitution to justify the federal overreach—the states' constitutional remedy is to amend the Constitution to clarify the meaning of the clauses that have been perverted. In this way, the states can assert their authority to close the loopholes the Supreme Court has opened.

You don't have to take my word for it.

In an 1830 letter to Edward Everett, James Madison said:

Should the provisions of the Constitution as here reviewed be found not to secure the Govt. & rights of the States agst. Usurpations & abuses on the part of the U.S. the final resort within the purview of the Constn. lies in an amendment of the Constn. according to a process applicable by the States.

In other words, Article Five is the ultimate nullification procedure. For states that have the will to stand up and assert their 10th Amendment rights, they can do so by applying for an Article Five convention to propose amendments that restrain federal power.

Rita Martin Dunaway serves as Staff Counsel for The Convention of States Project and is passionate about restoring constitutional governance in the U.S. Follow her on Facebook (Rita Martin Dunaway) and e-mail her at rita.dunaway@gmail.com.

The Article Five solution – the absurdity of inaction

Posted by Rita Dunaway on March 10, 2015 source

This is the second installment of a five-part series on Article V, written by staff counsel Rita Dunaway. The first part was originally published on TheBlaze.com and garnered 7,100 Facebook shares and was viewed 14,511 times. Read the first part on The Blaze here and the following article here.

Far and away, fear is the most common rationale among opponents of Article Five's convention process for proposing constitutional amendments. Fear of the uncertain result, fear of a Congressional take-over, fear of George Soros and what his money might buy.

But even as naysayers sit in their meeting rooms and chatrooms opining about hypothetical rogue delegates to a hypothetical convention, Congress continues to spend money that our great-grandchildren will one day owe.

Our president continues to use creative legal arguments to erase the lines that once separated constitutional powers, thrusting himself into the business of lawmaking.

Unelected bureaucrats continue to churn out mountains of regulations that are unauthorized by Congress—and in some cases put hardworking Americans out of work.

And the Supreme Court is one vote away from a revocation-through-interpretation of our right to bear arms.

Rather than checking and balancing one another as they were designed and empowered to do, the three branches of the federal government are acting in concert to further concentrate their power at the expense of state prerogatives and individual liberty.

All three branches are, effectively, making laws. Congress, the intended lawmaking branch, has extended its lawmaking into matters reserved to the states. And our unaccountable Supreme Court finds inventive ways to interpret the Constitution so as to justify this—not because it can't determine the Constitution's original meaning, but because the original meaning doesn't matter if our Constitution is, as we are told, a “living, breathing document.”

Meanwhile, administrative agencies—the bold and unmanageable fourth branch of government—have broken the will of the American people by the sheer volume of their regulations, rules and reports. The Environmental Protection Agency's 376-page “Regulatory Impact Analysis” for its War on Coal begins with a five-page list of acronyms to be learned by the aspiring reader—a virtual electric fence to all but the most intrepid citizen.

How can we be a self-governing people when we are completely removed from the invisible hands that actually regulate us, with no means of holding them accountable, and no hope of knowing or understanding the laws they are making?

Many who oppose using Article Five's convention process would agree that well-designed constitutional amendments could close court-created structural loopholes that have damaged our federal structure and concentrated power in Washington, D.C. For instance, we could require congressional approval for all administrative regulations. We could clarify where Congress' authority ends and the states' authority begins so that Congress could actually have time to do its constitutional job.

Yet some insist that an amendment-proposing convention amounts to open-heart surgery for our Constitution, and that nothing could ever justify such an action.

Newsflash: our beloved Constitution has been on the operating table, under the knife of an activist Supreme Court, for decades.

An admittedly imperfect but well-prepared team of doctors is standing by, eager to stop the bleeding and close up the wound. But a fearful crowd of skeptics is blocking the way. They love this patient and are not entirely convinced that the doctors' training is sufficient. Do they have the proper supplies? What if armed gunmen enter the surgical ward and interrupt the lifesaving process?

“No,” the skeptics conclude. “We can't be assured of a good outcome, so we had better just stand by.”

And the patient's life ebbs away.

We could learn a lot from Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the German pastor who resolved to actively resist Adolf Hitler, at any cost. Bonhoeffer had a painful understanding that it is our actions—not our sentiments—that reveal our truest convictions, and that our desire for safety can be an obstacle to the action that our professed morality requires. In 1934, he explained:

There is no way to peace along the way of safety. For peace must be dared, it is itself the great venture and can never be safe. Peace is the opposite of security.

It was also Bonhoeffer who said, “Not to act is to act.”

The Founding Fathers gave us a tool in Article Five to restrain federal power through state-proposed constitutional amendments. I do not doubt that the conservatives trying to block the use of this tool have sincere reverence for our founding document. But mere sentiments cannot rescue our Constitution from continued disfiguration under the federal scalpel, nor close the wounds that are standing open even as we continue this debate.

Rita Martin Dunaway serves as Staff Counsel for The Convention of States Project and is passionate about restoring constitutional governance in the U.S. Follow her on Facebook (Rita Martin Dunaway) and e-mail her at rita.dunaway@gmail.com.

<< Newer entries | Older entries >>