Table of Contents

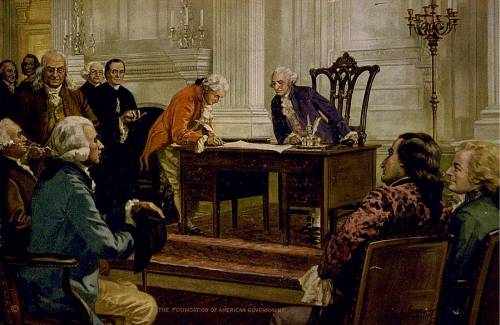

Convention of States opponents deny history to spread fear and misinformation

Posted by Rita Dunaway on April 28, 2016

I know I'm not the first to complain about the tendency of conservatives to give in when they should be standing their ground.

For a classic example of the problem, think back on the debacle that unfolded in Indiana last year, when officials caved to pressure instead of standing behind a supremely reasonable bill designed to protect people of faith against coercion to violate their consciences. When opponents of the bill got loud in proclaiming that it was a form of discrimination against people based on their sexual orientation, conservatives gave in to the bullying. The end result was a law that effectively makes sexual preference a higher-order interest than religious liberty.

Each time conservatives cut and run in this fashion, it reinforces the perception that we don't really believe what we say we believe. It also legitimizes the accusations of opponents who claim that the good, positive rationale behind the policies we initiate (concern for religious liberty) are just smokescreens for some base, sinister motivations (homophobia).

If it weren't bad enough that we do this with specific public policy issues, it appears that some conservatives are now relinquishing a core conservative value: the significance of history and original meaning in interpreting the Constitution.

One example of this is found in a list of “20 Questions” the conservative activist group Eagle Forum uses in opposing efforts by state legislatures to invoke the Constitution's Article Five process for states to initiate the proposal of constitutional amendments (a process Eagle Forum misleadingly refers to as a “constitutional convention”). The short-term goal of this list and countless articles that rely on the same “questions” is obvious: to spread fear and doubt so as to stymie state legislative resolutions that would trigger an amendment-proposing convention. Sadly, though, their broader effect is to not only throw part of our Constitution under the bus, but - perhaps unwittingly - to throw the originalist canon of interpretation under the bus right along with it.

The “questions” that Eagle Forum states “cannot be answered” include such significant matters as how convention delegates are selected, who determines the number of delegates for each state, and how convention rules will be determined.

While these surely are important questions about details that are not specifically spelled out in Article Five, Eagle Forum and others are wrong to suggest that the absence of explicit answers in the constitutional text means we are left to fumble around in the dark with nothing better than competing contemporary opinions to point the way. They are wrong because we have historyto guide us - the same history that originalists claim as our guide in correctly interpreting and applying every other part of the Constitution.

And that history is overwhelmingly clear on all of the truly essential questions naysayer conservatives shrug off as unanswerable. It is also readily accessible to anyone who cares to read it in the form of Mark Levin’s book The Liberty Amendments, as well as a treasure trove of peer-reviewed law review articles and shorter pieces by Professor Robert Natelson and others.

It is inconceivable that the leaders of a respectable organizations like Eagle Forum are simply unaware of the history surrounding interstate conventions and Article Five itself. Thus, the only conclusion one can draw from their ostensible bewilderment about the Article Five convention process is that they find history an insufficient guide in providing the basic answers. It's as if they have taken their cue from Supreme Court Justice Lewis Powell, who said, “After two centuries of vast change, the original intent of the Founders is difficult to discern or is irrelevant.”

I don't mean to suggest that Eagle Forum has suddenly and decisively abandoned originalism and wholeheartedly embraced the idea of a “living Constitution.” But merely that, whether intentional or not, their conclusion - that an Article Five convention should be feared because we allegedly have no idea how the process works - is absolutely a step in that direction.

Conservatives can't have it both ways. Either history supplies the meaning of constitutional language or it doesn't. And if it does, then the Article Five convention process for proposing amendments is a clear, well-lit path to the restoration of our federal system.

The interpretation of the Constitution according to the historical meaning of the text ought to be a hill that conservatives are willing to die on. And here's why: if we aren't really committed to conserving the meaning of constitutional language, then we have no greater basis for our position on constitutional interpretation than that we simply prefer it. Once unmoored from the historical fact of the Constitution's meaning, we are left adrift in a sea of opinion about what it “should” mean, or, ultimately, what we would like for it to mean. And when that is all there is to constitutional interpretation, what we have is the rule of men (whoever is in power decides what the Constitution means according to his own predilections) rather than the rule of law (the Constitution has a definite meaning to be ascertained and obeyed).

I can understand the reluctance of some to take a firm stand on whether the states should use their Article Five check on federal power, in light of the fact that some conservatives are afraid to truly take on the federal behemoth.

But I am sorely disappointed and more than a little shocked to see any conservative ignore the solid answers of history in order to manufacture doubt about a constitutional process. In doing so, they strain out a gnat only to swallow a camel - a hypocrisy in what they really believe about interpreting and applying our beloved Constitution.

Rita Martin Dunaway serves as National Legislative Strategist for the Convention of States Project.

This article was originally published on The Blaze.

Hilarious video: The best bad arguments against a Convention of States

Posted by Convention of States Project on April 20, 2016

We've heard some fantastically bad arguments over the years, but these state legislators take the cake. Here are some of the best of the worst.

Make the feds play by the real rules

Posted by Rita Dunaway on December 23, 2015 (source)

I recently watched, flabbergasted, as two of my nieces played a game of chess outdoors with giant chess pieces. What astounded me was not the size of the pieces, but rather the fact that they appeared to be playing two different games, and yet purported to be competing. When I inquired about this, my suspicions were confirmed. While my older niece attempted to compete at chess according to the actual rules of chess, my younger niece was indiscriminately capturing queens, rooks and pawns alike by simply “jumping” them. She was playing “chess” according to the rules of checkers.

It is an apt analogy of what is happening to American government. While the states, for the most part, attempt to do what they were designed and empowered to do under the Constitution — enact laws for the health, safety, and welfare of the people and experiment with public policies based upon the particular needs and desires of their populations — the national government in Washington, D.C., is playing by its own set of rules.

You probably thought I meant that figuratively, but in fact, I meant it quite literally.

Washington, D.C., is now operating not on the basis of the original Constitution that can easily be read and digested in the space of an hour, but rather on the basis of a 3,000-page version of the Constitution known as the “Constitution Annotated.” It contains not only the plain and simple text of our beloved founding document, but also the perversions to the original text made by a litany of Supreme Court precedents that, to date, enjoy “supreme law of the land” status.

You know — the “interpretations,” piling up since as early as 1928, that allow mountains of laws to be created by unelected bureaucrats instead of elected members of Congress. The “interpretation” that allows Congress, under the Interstate Commerce clause, to regulate what a single farmer plants in his field. The “interpretation” that says Congress can “tax” individuals for refusing to engage in a particular economic transaction. The “interpretation” that Congress may use a virtually unlimited taxing and spending power to bully states into enacting the laws that Congress wants them to have.

Together with scores of others, these “interpretations” have effectively —albeit illegitimately — amended the federal government's operating manual.

What many Americans don't realize is that the states, collectively, have all the power they need to overturn those “interpretations” — legitimately and authoritatively — and to reinstate and clarify the original meaning of constitutional language that has succumbed to federal distortion.

By using the state-controlled process of initiating corrective constitutional amendments through Article Five of the U.S. Constitution, the states have every opportunity to reinvigorate the truly federal system designed for a nation of liberty-loving, self-governing people.

If you want to see a renaissance of American federalism, with a strictly limited national government and state governments creating the policies best suited to their own citizens, urge your state legislators to support resolutions triggering an amendment-proposing convention to rein in federal power. Chances are, your state will be considering it early in 2016, so now is the time to make your voice heard.

You see, the truly astounding thing about the game of “chess” that my nieces played together was not that the younger niece flouted the rules in a way that gave her all the advantage. The truly astounding thing was that my older niece allowed her to continue doing it.

It is said that “we get the government we deserve.” Will we do our part to insist that our state legislators use their constitutional power to repair the federal machine? Or will we watch passively as Washington, D.C., plays by its own, constantly-evolving version of the rules?

Rita Martin Dunaway serves as National Legislative Strategist for the Convention of States Project. Contact her at rdunaway@cosaction.com, or follow her on facebook.

Click here to read more from The Blaze.

The 10th Amendment doesn't give states power to amend

Posted by Convention of States Project on December 18, 2015 (source)

Some advocates of a convention for proposing amendments are endangering the Article V movement by claiming the states can use the Tenth Amendment to control the convention process. They are doing so even though the judiciary, including the U.S. Supreme Court, has held that state legislatures' Article V powers come from the Constitution directly, not from the Tenth Amendment.

We have been down this road before: During the 1980s and 1990s, balanced budget and term limits activists adopted procedures based on the Tenth Amendment. The courts voided those procedures repeatedly.

Those resting new campaigns on the Tenth Amendment risk the same fate. They could set back the Article V process for decades, just as judicial defeats in the 1980s and '90s stalled it for over 20 years.

Here's the constitutional law background:

The Tenth Amendment provides that “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.”

As I point out in my book, The Original Constitution, the Ninth Amendment was supposed to be the principal statement of federalism. The Tenth was designed chiefly to clarify that the federal government would not have any extra-constitutional powers of the kind that leaders such as James Wilson had claimed for the Confederation Congress under the supposed doctrine of “inherent sovereign authority.”

Nevertheless, both modern courts and modern commentators accept the Tenth as a broad statement of federalism, and the following discussion does so as well.

The Tenth Amendment is a rule of construction—that is, a clarifying rather than substantive amendment. It explains that “powers not delegated” are reserved. It obviously does not apply to powers that the Constitution DOES delegate. See U.S. v. Darby Lumber (1941).

In Hawke v. Smith No. 1 (1920), the U.S. Supreme Court held that the functions performed by Congress and state legislatures under Article V come directly from the Constitution—i.e., they are delegated by the people through that document. The Court confirmed this analysis shortly thereafter in a case called Leser v. Garnett (1922). Both cases invalidated efforts to control the amendment process though state law.

These cases clarified that when Congress, state legislatures, and conventions operate under Article V, they do so as independent assemblies, not as branches of government. This is the same approach the Supreme Court applies to the Electoral College. Ray v. Blair (1951). The Supreme Court says that non-governmental entities exercising authority directly under the Constitution perform “federal functions.” See Leser.

At this point, it should already be clear that the Tenth Amendment does not apply to the constitutional amendment process. Article V delegates power to entities (legislatures, conventions), which exercise them on behalf of “the United States” (although not on behalf of the government). But the Tenth Amendment applies only to powers “not delegated.”

Thus, in United States v. Thibault, a federal appeals court, using a slightly different analysis, held that the Tenth Amendment did not apply to the amendment process—that it “does not alter the fifth article.” Later that year, the Supreme Court held in United States v. Sprague (1931) that the Tenth Amendment had no application to Article V's grants of power to Congress.

One might point out that the Thibault and Sprague cases involved Congress's role in the process, not the role of the states. But the opinions in those cases make clear that the judges deciding them were applying the same principles to Congress that the Supreme Court had applied earlier to state legislatures.

If any doubt remained, the Supreme Court resolved it in 1995, when it decided U.S. Term Limits v. Thornton. In that case, Arkansas had tried to use powers reserved by the Tenth Amendment to force term limits on its congressional delegation. However, the Supreme Court held that the Tenth Amendment's reservation of state authority applied only to authority the states enjoyed previous to the Constitution. The Court said the Tenth Amendment did not apply to authority created by the Constitution.

The Court said:

. . . [T]he power to add qualifications is not part of the original powers of sovereignty that the Tenth Amendment reserved to the States . . . [T]hat Amendment could only “reserve” that which existed before. As Justice Story recognized, “the states can exercise no powers whatsoever, which exclusively spring out of the existence of the national government, which the constitution does not delegate to them. No state can say, that it has reserved, what it never possessed.”

****

This conclusion is consistent with our previous recognition that, in certain limited contexts, the power to regulate the incidents of the federal system is not a reserved power of the States, but rather is delegated by the Constitution. . . . Cf. Hawke v. Smith, No. 1, 253 U.S. 221, 230, 40 S.Ct. 495, 64 L.Ed. 871 (1920) (“[T]he power to ratify a proposed amendment to the Federal Constitution has its source in the Federal Constitution. The act of ratification by the State derives its authority from the Federal Constitution to which the State and its people have alike assented”).

Note the explicit comparison with the amendment process and the citation of Hawke v. Smith. The reason the Hawke case was relevant was that the state powers under Article V are conferred by the Constitution. They did not exist before that document came into effect. So the Tenth Amendment does not apply to them.

Rob Natelson is Senior Fellow in Constitutional Jurisprudence, Independence Institute, Heartland Institute & Montana Policy Institute, and Professor of Law (ret.), The University of Montana. biography & bibliography: http://constitution.i2i.org/about/

Read more from the American Thinker here.

How the procedures for a modern Amendments Convention may unfold

Posted by Convention of States Project on December 17, 2015 (source)

The following article is the final edition of a 6-part series by Prof. Robert Natelson addressing conventions for proposing constitutional amendments. Prof. Natelson retired a few years ago from the University of Montana School of Law and is now senior fellow in constitutional jurisprudence at the Independence Institute; his work has been cited in five Supreme Court cases since 2013.

[ Part 1 - Part 2 - Part 3 - Part 4 - Part 5 - Part 6 ]

Parts I to V of this series discussed the background and nature of the Constitution's “Convention for proposing Amendments.” This final installment surveys the most likely scenarios for calling a convention, and possible developments if 34 states apply on any one subject or an overlapping group of subjects.

The subject matter for amendments submitted to a convention will depend on which of several application drives induces Congress to issue the first call.

The possibilities are complicated by the fact that some applications are vulnerable legally. For example, convention opponents have argued that applications that are “too old” are invalid or “stale” on that account. This argument was significantly weakened by adoption of the 27th amendment, in which unrepealed ratifications two centuries old were accepted as valid. More serious is the fact that many extant applications purport to limit the convention to considering only an amendment with prescribed wording. That may render them inherently invalid or inaggregable with more general applications.

The number of unrepealed applications is in the hundreds, although no one subject has attained the threshold of 34. Some are from now-abandoned campaigns, such as those for banning polygamy and repealing the 16th amendment (which dropped the apportionment requirement for the income tax). The application totals are at the website of the Article V Library.

Among the currently active campaigns, the frontrunner is the Balanced Budget Amendment Task Force, which claims applications from 27 states.

In 2014, Citzens for Self-Governance began its “Convention of States” project. Relying on grass-roots enthusiasm, it has won the endorsement of four state legislatures. All four applications closely track the form recommended by “Convention of States” activists: They would empower the convention to consider fiscal restraints on the federal government, term limits and reductions in federal power.

Also enjoying the endorsement of four states is the Wolf PAC movement, which seeks campaign finance reform. Realistically, Wolf PAC is unlikely to reach the threshold of 34. This is partly because of the conservative political composition of most state legislatures and partly because not all of its applications are fully consistent. In addition, while the general idea of campaign finance reform enjoys strong public support, most specific proposals involve granting more power to Congress. This is a tough sell at a time when the electorate is deeply dissatisfied with Congress.

Other Article V campaigns include those aiming to impose a single subject rule on Congress, a revived push for congressional term limits and the Act 2 Movement, which promotes term limits, fiscal restraints, campaign finance reform and creation of a fourth branch of government to enforce the law against the other three.

Once a campaign claims to have reached the 34-state minimum, Congress will have to determine whether the applications truly “aggregate” with each other. If the campaign is for a balanced-budget amendment, Congress may have to exercise some discretion. Although most balanced-budget applications simply demand a convention to consider the subject, three purport to limit the convention to prescribed language. Congress may have to determine whether to aggregate the two sets. Congressional discretion also may be necessary to decide whether applications that demand an unlimited convention should be included in the total.

How Congress reacts will, of course, be influenced by the then-current political environment. I have stressed to state legislators the need to communicate forcefully both to Congress and the general public the conditions under which Congress must call and the proper limits of a call. State legislative planners have responded well to this advice.

Interstate conventions held earlier in our history included commissioners who had attended prior interstate conventions. Because that sort of experience is lacking today, state legislative planning groups have sprung up to prepare: the State Legislators Article V Caucus, the Assembly of State Legislatures and the Convention of States Caucus. In addition, two trade organizations of state lawmakers, the National Conference of State Legislatures and the American Legislative Exchange Council, have presented programs on convention issues.

Necessarily, there have been some mistakes. Recently the executive committee of the Assembly of State Legislatures recommended to the general membership an impractical system of convention rules mandating supermajorities and weighted voting, and even co-presidents and co-committee chairs from opposite parties. The general membership's firm rejection of those rules suggests that wisdom is likely to prevail over the long term, and that when a convention does meet it will have the benefit of a viable procedural template.

Earlier this year, I undertook a study of prior convention rules to ascertain their modern applicability. Here are some of my conclusions:

- Most of the rules applied at 18th- and 19th-century conventions are still viable. In fact, some these rules are echoed in modern legislative practice.

- Any set of convention rules must be supplemented by default rules. For this purpose, I recommended “Mason’s Manual,” by far the most commonly used rulebook in American state legislatures. Both the Assembly of State Legislatures and the Convention of States project have adopted this recommendation.

- The principles of one state/one vote and decision-by-simple-majority sometimes have been challenged, but ultimately every convention has retained or returned to them for most purposes.

- Although in theory a bare majority of low-population states could cause the convention to propose an unpopular amendment, modern political conditions render this highly improbable.

- Ratification is quite a different process from proposal. A proposal's margin of victory at the convention is probably not a strong predictor of whether or not it is ratified.

- Some traditional rules will have to be modified. For example, rules barring commissioners from access to written materials will yield to the world of electronic hand-held devices. Traditional rules of secrecy will yield to modern values of transparency.

- In prior conventions, the distances between the state capital and the convention site required most legislatures to rely heavily on their commissioners' discretion once those commissioners had received their initial instructions. Modern communications will enable commissioning authorities to exercise more influence on their representatives. On balance, this is probably a good development, since it reduces the chance of commissioners exceeding their authority, and it involves a wider group in the negotiating process.

- A modern 50-state convention probably will consist of between 200 and 250 commissioners. Some states may appoint alternates as well. Each state legislature is free to fix the size of its own “committee,” but at my suggestion most planners are contemplating convention rules that limit the number of commissioners on the floor from any state at any one time. This will reduce the incentives for states to flood the assembly, as Tennessee did at the 1850 Nashville convention.

- Some states may boycott, as Rhode Island boycotted the Constitutional Convention. Over the three-plus centuries of American multi-government conventions, none has ever attained 100 percent participation.

- Whether or not a modern convention actually proposes an amendment, and whether any such amendment is ratified, the event will provoke new public interest in our constitutional system. It may also revivify awareness of the role of the states in American federalism.

Click here for more from The Washington Post.